Preschoolers and Toddlers, Diet of

At approximately age one, children enter the latent period of growth. During this period, until the onset of puberty , growth and development are more gradual than during the first year. Physical growth steadies, and the body begins to look more proportioned as it prepares for an "upright" lifestyle .

The immediate stages following infancy are toddlerhood (ages one through three) and the preschool years (ages three through five). Characterized by temper tantrums, exploration, and endless questions, these periods can be trying for parents. Individual children experience growth spurts and plateaus —during which growth seems to stop completely. Food intake, and a liking of certain foods, may change constantly, causing a great deal of anxiety for parents.

Parents need to recognize that these changes are a normal part of development. Understanding the nutritional requirements of these age groups may help parents adapt to the new challenges. In addition, parents should be aware of the potential problems associated with feeding young children—and the ways to prevent them.

Nutritional Requirements

Compared to adults, small children need more nutrients in proportion to their body weight. As bones, muscles, teeth, and blood volume are developing,

![Former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Dan Glickman promotes federal food programs at a daycare center while the children behind him enjoy lunch. [Photograph by Mike Derer. AP/Wide World Photos. Reproduced by permission.]](../images/nwaz_02_img0194.jpg)

The Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs), which include the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) and Adequate Intakes (AIs), should serve as a guide to prevent deficiencies in this age group. However, most of the levels set for preschoolers and toddlers are based on values established for infants and adults. In addition, the DRIs include a built-in margin of safety that exceeds the requirements for most children in the United States. Therefore, an intake that is less than that specified in the DRIs is not necessarily a reason for concern. For parents, a more practical approach to ensuring proper nutrient intake is to use the Food Guide Pyramid for Young Children, devised by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).0

Most people do not follow the requirements specified in these guides. Although severe nutrient deficiencies are rare in the United States, calcium , iron , zinc , vitamin B6, folic acid, and vitamin A are the nutrients most likely to be low in children as a result of poor dietary habits. Ensuring that children eat the recommended number of servings from each of the food groups in the pyramid is the best way to be certain that all nutritional requirements are met. A good rule of thumb for serving sizes is one tablespoon per year of age.

Energy and Protein Needs.

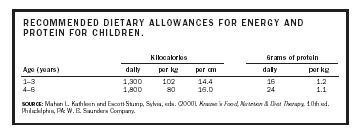

Basal metabolic rate , growth, and physical activity all affect a child's daily energy. Regardless of the total intake, the composition should resemble the following: 50 to 60 percent of calories from carbohydrates , 25 to 35 percent of calories from fat, and 10 to

| Age (years) | Kilocalories | Grams of protein | |||

| daily | per kg | per cm | daily | per kg | |

| SOURCE: Mahan L. Kathleen and Escott-Stump, Sylvia, eds. (2000). Krause's Food, Nutrition & Diet Therapy, 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Company. | |||||

| 1–3 | 1,300 | 102 | 14.4 | 16 | 1.2 |

| 4–6 | 1,800 | 80 | 16.0 | 24 | 1.1 |

15 percent of calories from protein (see accompanying table.) It should be remembered, however, that this is simply an estimate, and intake may need to be adjusted to suit each child.

Protein is a vital dietary component for preschoolers and toddlers, as it is needed for optimal growth. Enough protein should be consumed every day to allow for proper development. Protein deficiencies are rare in the United States, since most U.S. children consume plenty of protein each day. When protein malnutrition does occur, it is usually seen in those from low-income homes, those who follow a strict vegan diet excluding all animal sources, and those with multiple food allergies .

Vitamin and mineral needs.

Iron is a vital component of hemoglobin , the carrier of oxygen in the blood. As a young child grows, blood volume increases, and so does the need for iron. Preschoolers and toddlers typically eat less iron-rich foods than they did in infancy. In addition, the iron that children get is usually non-heme iron (from plant sources), which has a lower availability than heme iron (from animal sources). As a result, children up to three years of age are at high risk for iron-deficiency anemia . The RDA for iron for both toddlers and preschoolers is ten milligrams (mg) per day.

Calcium is needed for bone and teeth mineralization and maintenance. The amount of calcium a child needs is determined in part by the consumption of other nutrients, such as protein, phosphorus and vitamin D , as well as the child's rate of growth. During this period of development, children need two to four times as much calcium per kilogram of body weight as adults do. The AI for toddlers is 500 mg/day, while for preschoolers it is 800 mg/day. Since dairy foods are the primary source of calcium, children who do not consume enough dairy or have an aversion to dairy products may be at risk for calcium deficiency.

The body can produce vitamin D in the skin in response to sun exposure. The amount of vitamin D needed daily thus depends mainly on how much time a child spends outside and on geographical location. The RDA for children living in tropical areas is between zero and 2.5 micrograms (μg) per day, depending on the amount of sun exposure. For those living in temperate zones , the RDA increases to 10 mc/day. Vitamin D–fortified milk is the best source.

Zinc is essential for proper development. It is needed for wound healing, proper sense of taste, proper growth, and normal appetite. Preschoolers and toddlers are sometimes at risk for marginal zinc deficiencies because the best sources are meats and seafoods, foods they may not eat regularly. The recommended intake of zinc is 10 mg/day.

Vitamin and mineral supplements are popular with more than 50 percent of parents of preschoolers and toddlers. Most use a multivitamin/mineral supplement with iron. Parents should be aware, however, that such supplements do not necessarily fulfill the needs for marginal or deficient nutrients. For example, although calcium is often a nutrient that is low in children, most multivitamin/mineral supplements do not include it, or include it in very low doses. The American Academy of Pediatrics does not support routine supplementation for normal, healthy kids. Although there is no harm in giving children a standard children's supplement, megadoses should always be avoided, and caution should be used when supplementing the fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E, and K).

Potential Feeding Problems

As young children develop their likes and dislikes and learn to feed themselves, parents need to allow them to become more independent. As a result of these changes, potential concerns arise. Common feeding problems among preschoolers and toddlers are: obesity , nursing bottle mouth syndrome, food jags, and iron-deficiency anemia.

According to the national Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System, 10.2 percent of children in the United States under the age of five were overweight in 1998. These rates have been increasing steadily since the 1960s. Prevention education is the key to lowering the incidence of obesity in children. Success has been shown in programs that include family involvement, nutritional information and modification, activity planning, and behavior therapy.

Most often seen in children under age three, nursing bottle mouth syndrome (or baby bottle tooth decay) results from extended bottle feeding. It occurs when a child is routinely given a bottle with sweetened beverages (such as milk or juice) at bedtime. As the child sleeps, the liquid pools around the teeth. The result is severe caries on the incisors and cheek surfaces of molars . Parents should avoid giving a bottle at bedtime and begin serving beverages in a cup as early as possible.

Most children undergo a normal part of development know as a food jag. Food jags occur when children either refuse to eat a previously accepted food, or when they insist on eating one particular food all the time. A food jag is generally a case of a child testing his or her independence. Although annoying for most parents, food jags are rarely a reason for concern. The best strategy is to continue offering a variety of foods every day, while keeping the favorite food available. Most children will eventually return to a normal eating pattern. Letting a food jag take its course is the best plan of action; force will accomplish little.

Feeding Strategies for Parents

• Allow kids to eat five to six small meals per day.

• Allow them to eat when they are hungry and do not force them to eat when they are not.

• Do not use food as a reward or punishment.

• Be aware of the risk of choking in these age groups. Avoid foods that are round, hard, or do not easily dissolve in saliva (such as hot dogs, grapes, raw vegetables, popcorn, nuts, peanut butter, and hard candy).

• Avoid feeding too many sweetened beverages (especially in the bottle); encourage them to drink plenty of water.

Despite the wide availability of iron-rich foods, iron-deficiency anemia is the most common nutrient deficiency in the world. Reasons for this deficiency in toddlers may be the consumption of large quantities of milk, and thus limited intake of solids and iron-fortified foods. In addition, many young children do not like the best sources of iron, such as meats and seafoods. Parents should pay special attention to include good dietary sources of iron in their children's diet. When meat or seafood sources are limited, the availability of iron from plant sources can be increased with the consumption of ascorbic acid (vitamin C).

The preschool and toddler years often create anxiety in parents as food likes, dislikes, and requirements may change continuously. Understanding that these changes are a normal part of development, and understanding the nutritional requirements for this age group, will help parents make educated decisions. Parents should also be aware of the potential feeding problems of this group, and of the ways to prevent them.

SEE ALSO Baby Bottle Tooth Decay ; Childhood Obesity .

Kirsten Herbes

Bibliography

Ballabriga, Angela, ed. (1996) Feeding from Toddlers to Adolescence. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven.

Duyff, Roberta L. (1998). The American Dietetic Association's Complete Food & Nutrition Guide. Minneapolis, MN: Chronimed Publishing.

Herbest, Victor, and Subak-Sharpe, Genell J., eds. (1995). Total Nutrition: The Only Guide You'll Ever Need. New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin.

Hovasi Cox, Jance, ed. (1997) Nutrition Manual for At-Risk Infants and Toddlers. Chicago, IL: Precept Press.

Mahan, L. Kathleen, and Escott-Stump, Sylvia, eds. (2000). Krause's Food, Nutrition, and Diet Therapy, 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Company.

McWilliams, Margaret (1986). Nutrition for the Growing Years. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Queen Samor, Patricia; King Helm, Kathy; and Lang, Carol E. (1999). Handbook of Pediatric Nutrition, 2nd ed. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, Inc.

Tamborlane, William V., ed. (1997). The Yale Guide to Children's Nutrition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wardlaw, Gordon M. (1999). Perspectives in Nutrition, 4th ed. New York, NY: WCB/McGraw-Hill.

Internet Resources

American Dietetic Association. "Child Feeding." American Dietetic Association. Available from <http://www.eatright.com/healthy/child/>

American Dietetic Association. "Position of the ADA: Dietary Guidance for Healthy Children Aged 2 to 11 years." Available from <http://www.eatright.com/adap0199.html>

American Dietetic Association. "Food Guide Pyramid for Young Children." Available from <http://www.usda.gov/cnpp/kidspyra>

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: