Calcium

Calcium is one of the most important elements in the diet because it is a structural component of bones, teeth, and soft tissues and is essential in many of the body's metabolic processes. It accounts for 1 to 2 percent of adult body weight, 99 percent of which is stored in bones and teeth. On the cellular level, calcium is used to regulate the permeability and electrical properties of biological membranes (such as cell walls), which in turn control muscle and nerve functions, glandular secretions, and blood vessel dilation and contraction. Calcium is also essential for proper blood clotting .

Because of its biological importance, calcium levels are carefully controlled in various compartments of the body. The three major regulators of blood calcium are parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D , and calcitonin. PTH is normally released by the four parathyroid glands in the neck in response to low calcium levels in the bloodstream (hypocalcemia). PTH acts in three main ways: (1) It causes the gastrointestinal tract to increase calcium absorption from food, (2) it causes the bones to release some of their calcium stores, and (3) it causes the kidneys to excrete more phosphorous, which indirectly raises calcium levels.

Vitamin D works together with PTH on the bone and kidney and is necessary for intestinal absorption of calcium. Vitamin D can either be obtained from the diet or produced in the skin when it is exposed to sunlight. Insufficient vitamin D from these sources can result in rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults, conditions that result in bone deformities. Calcitonin, a hormone released by the thyroid, parathyroid, and thymus glands, lowers blood levels by promoting the deposition of calcium into bone.

Most dietary calcium is absorbed in the small intestine and transported in the bloodstream bound to albumin, a simple protein . Because of this method of transport, levels of albumin can also influence blood calcium measurements. Calcium is deposited in bone with phosphorous in a crystalline form of calcium phosphate.

Deficiency and Toxicity

Because bone stores of calcium can be used to maintain adequate blood calcium levels, short-term dietary deficiency of calcium generally does not result in significantly low blood calcium levels. But, over the long term, dietary deficiency eventually depletes bone stores, rendering the bones weak and prone to fracture. A low blood calcium level is more often the result of a disturbance in the body's calcium regulating mechanisms, such as insufficient PTH or vitamin D, rather than dietary deficiency. When calcium levels fall too low, nerve and muscle impairments can result. Skeletal muscles can spasm and the heart can beat abnormally—it can even cease functioning.

Toxicity from calcium is not common because the gastrointestinal tract normally limits the amount of calcium absorbed. Therefore, short-term intake of large amounts of calcium does not generally produce any ill effects aside from constipation and an increased risk of kidney stones . However, more severe toxicity can occur when excess calcium is ingested over long periods, or when calcium is combined with increased amounts of vitamin D, which increases calcium absorption. Calcium toxicity is also sometimes found after excessive intravenous administration of calcium. Toxicity is manifested by abnormal deposition of calcium in tissues and by elevated blood calcium levels (hypercalcemia). However, hypercalcemia is often due to other causes, such as abnormally high amounts of PTH. Usually, under these circumstances, bone density is lost and the resulting hypercalcemia can cause kidney stones and abdominal pain. Some cancers can also cause hypercalcemia, either by secreting abnormal proteins that act like PTH or by invading and killing bone cells causing them to release calcium. Very high levels of calcium can result in appetite loss, nausea , vomiting, abdominal pain, confusion, seizures, and even coma.

Requirements and Supplementation

Dietary calcium requirements depend in part upon whether the body is growing or making new bone or milk. Requirements are therefore greatest during childhood, adolescence, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Recommended daily intake (of elemental calcium) varies accordingly: 400 mg for

![Calcium supplements can help prevent osteoporosis, which is a condition that occurs when bone breaks down more quickly than it is replaced. In this illustration, the bone above is normal, but the bone below is more porous and therefore more susceptible to fracture. [Custom Medical Stock Photo, Inc. Reproduced by permission.]](../images/nwaz_01_img0043.jpg)

Calcium absorption is affected by many factors, including age, the amount needed, and what foods are eaten at the same time. In general,

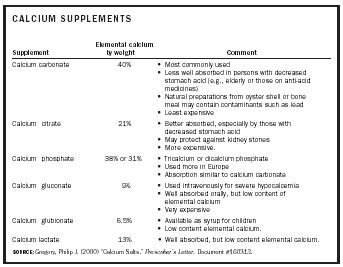

| Supplement | Elemental calcium by weight | Comment |

| Calcium carbonate | 40% |

• Most commonly used

• Less well absorbed in persons with decreased stomach acid (e.g., elderly or those on anti-acid medicines) • Natural preparations from oyster shell or bone meal may contain contaminants such as lead • Least expensive |

| Calcium citrate | 21% |

• Better absorbed, especially by those with decreased

stomach acid

• May protect against kidney stones • More expensive. |

| Calcium phosphate | 38% or 31% |

• Tricalcium or dicalcium phosphate

• Used more in Europe • Absorption similar to calcium carbonate |

| Calcium gluconate | 9% |

• Used intravenously for severe hypocalcemia

• Well absorbed orally, but low content of elemental calcium • Very expensive |

| Calcium glubionate | 6.5% |

• Available as syrup for children

• Low content elemental calcium. |

| Calcium lactate | 13% | • Well absorbed, but low content elemental calcium. |

| SOURCE : Gregory, Philip J. (2000) "Calcium Salts." Prescriber's Letter. Document #160313. | ||

calcium from food sources is better absorbed than calcium taken as supplements. Children absorb a higher percentage of their ingested calcium than adults because their needs during growth spurts may be two or three times greater per body weight than adults. Vitamin D is necessary for intestinal absorption, making Vitamin D–fortified milk a very well-absorbed form of calcium. Older persons may not consume or make as much vitamin D as is optimal, so their calcium absorption may be decreased. Vitamin C and lactose (the sugar found in milk) enhance calcium absorption, whereas meals high in fat or protein may decrease absorption. Excess phosphorous consumption (as in carbonated sodas) can decrease calcium absorption in the intestines . High dietary fiber and phytate (a form of phytic acid found in dietary fiber and the husks of whole grains) may also decrease dietary calcium absorption in some areas of the world. Intestinal pH also affects calcium absorption—absorption is optimal with normal stomach acidity generated at meal times. Thus, persons with reduced stomach acidity (e.g., elderly persons, or persons on acid-reducing medicines) do not absorb calcium as well as others do.

Calcium supplements are widely used in the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Supplements are also recommended, or are being investigated, for a number of conditions, including hypertension , colon cancer , cardiovascular disease, premenstrual syndrome, obesity , stroke , and preeclampsia (a complication of pregnancy). There are several forms of calcium salts used as supplements. They vary in their content of elemental calcium, the amount effectively absorbed by the body, and cost. Whatever the specific form, the supplement should be taken with meals to maximize absorption.

Calcium is one of the most important macronutrients for the body's growth and function. Sufficient amounts are important in preventing many diseases. Calcium levels are tightly controlled by a complex interaction of hormones and vitamins . Dietary requirements vary throughout life and are greatest during periods of growth and pregnancy. However, recent reports suggest that many people do not get sufficient amounts of calcium in their diet. Various calcium supplements are available when dietary intake is inadequate.

SEE ALSO Minerals ; Osteomalacia ; Osteoporosis ; Rickets .

Donna Staton Marcus Harding

Bibliography

Berkow, Robert, ed. (1997). The Merck Manual of Medical Information, Home Edition. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.

National Research Council (1989). Recommended Dietary Allowances, 10th edition. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Olendorf, Donna; Jeryan, Christine; and Boyden, Karen, eds. (1999). The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research.

Internet Resources

Food and Nutrition Board (1999). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorous, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Available from <http://www.nap.edu>

Gregory, Philip J. (2000) "Calcium Salts." Prescriber's Letter Document #160313. Available from <http://www.prescribersletter.com>

How much over the rec dosage of 1200mg/day & for how long? Months or years? Regular intake of calc from diet, but also tums almost daily (for digestive probs)...is this concern for kidney stones or any of the other more extreme side effects?

My nephrologist says this is Gout, but I can't find any reference to this in the symptomology of Gout. The Rheumatologist says she thinks it is Calcium related but is not doing anything to check or treat it.

I have also been experiencing loss of appetite, joint pain, significant weight loss (I've gone from size 8-10 to size 2-4), energy loss, stomach pain, loose bowel and formerly straight fingers are twisting and turning into pretzels.

I am becoming an invalid yet it is all being attributed to my kidney function which is poor but stable. My colesterol is normal except for a slightly low HDL and High PTH. I'm taking multi-vit. and calcium. Could this be a Calcium overdose problem?