African Americans, Diet of

The 2000 U.S. Census revealed that there were almost 35 million African Americans, or about 13 percent of the total U.S. population. This small percentage of the populace has had a significant influence on American cuisine, not only because African-American food is diverse and flavorful, but also because of its historical beginnings. Despite their cultural, political, economic, and racial struggles, African Americans have retained a strong sense of their culture, which is, in part, reflected in their food.

Origins of the African-American Diet: The Aftereffects of Slavery

The roots of the diversity of African-American cuisine may be traced back to 1619, when the first African slaves were sold in the New World. In a

![A major ingredient in cuisine of African origin, okra traveled to the eastern Mediterranean, Arabia, and India long before it came to the New World with African slaves. The thickening characteristic of its sticky substance is put to good use in the preparation of gumbos and stews. [Photograph by Robert J. Huffman/Field Mark Publications. Reproduced by permission.]](../images/nwaz_01_img0012.jpg)

It is not surprising that African-American food has a distinctive culinary heritage with diverse flavors, as it includes traditions drawn from the African continent, the West Indies, and from North America. While the European nations were busy establishing new societies, they did not realize that the African and West Indian slaves who worked for them brought their own vibrant and and rich culture—a culture that would withstand and adapt to the harsh centuries of slavery.

Food historian Karen Hess writes about the struggle of African Americans to maintain some of their original culture through food. "The only thing that Africans brought with them [from Africa] was their memories." Slave traders attempted to craft culturally sensitive rations for the Africans by including yams, rice, corn, plantains, coconuts, and scraps of meat in the slaves' provisions.

Southern slaves established their own cooking culture using foods that were similar to foods that were part of their African and West Indian heritages, and many popular foods in the African-American diet are directly associated with foods in Africa. For instance, the African yam is similar to the American sweet potato. White rice is also popular because it was a major part of the diet in West Africa. African Americans infuse plain rice dishes with their own savory ingredients (popular rice dishes include gumbo and "hoppin' John," a dish made with rice, black-eyed peas, and salt pork or bacon).

The Legacy of African-American Cuisine

Popular southern foods, such as the vegetable okra (brought to New Orleans by African slaves), are often attributed to the importation of goods from Africa, or by way of Africa, the West Indies, and the slave trade. Okra, which is the principal ingredient in the popular Creole stew referred to as gumbo, is believed to have spiritual and healthful properties. Rice and seafood (along with sausage or chicken), and filé (a sassafras powder inspired by the Choctaw Indians) are also key ingredients in gumbo. Other common foods that are rooted in African-American culture include black-eyed peas, benne seeds (sesame), eggplant, sorghum (a grain that produces sweet syrup and different types of flour), watermelon, and peanuts.

Though southern food is typically known as "soul food," many African Americans contend that soul food consists of African-American recipes that have been passed down from generation to generation, just like other African-American rituals . The legacy of African and West Indian culture is imbued in many of the recipes and food traditions that remain popular today. The staple foods of African Americans, such as rice, have remained largely unchanged since the first Africans and West Indians set foot in the New World, and the southern United States, where the slave population was most dense, has developed a cooking culture that remains true to the African-American tradition. This cooking is aptly named southern cooking, the food, or soul food. Over the years, many have interpreted the term soul food based on current social issues facing the African-American population, such as the civil rights movement. Many civil rights advocates believe that using this word perpetuates a negative connection between African Americans and slavery. However, as Doris Witt notes in her book Black Hunger (1999), the "soul" of the food refers loosely to the food's origins in Africa.

In his 1962 essay "Soul Food," Amiri Baraka makes a clear distinction between southern cooking and soul food. To Baraka, soul food includes chitterlings (pronounced chitlins), pork chops, fried porgies, potlikker, turnips, watermelon, black-eyed peas, grits, hoppin' John, hushpuppies, okra, and pancakes. Today, many of these foods are limited among African Americans to holidays and special occasions. Southern food, on the other hand, includes only fried chicken, sweet potato pie, collard greens, and barbecue, according to Baraka. The idea of what soul food is seems to differ greatly among African Americans.

General Dietary Influences

In 1992 it was reported that there is little difference between the type of foods eaten by whites and African Americans. There have, however, been large changes in the overall quality of the diet of African Americans since the 1960s. In 1965, African Americans were more than twice as likely as whites to eat a diet that met the recommended guidelines for fat , fiber , and fruit and vegetable intakes. By 1996, however, 28 percent of African Americans were reported to have a poor-quality diet, compared to 16 percent of whites, and 14 percent of other racial groups. The diet of African Americans is particularly poor for children two to ten years old, for older adults, and for those from a low socioeconomic background. Of all racial groups, African Americans have the most difficulty in eating diets that are low in fat and high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. This represents an immense change in diet quality. Some explanations for this include: (1) the greater market availability of packaged and processed foods ; (2) the high cost of fresh fruit, vegetables, and lean cuts of meat; (3) the common practice of frying food; and (4) using fats in cooking.

Regional differences.

Although there is little overall variability in diets between whites and African Americans, there are many notable regional influences. Many regionally influenced cuisines emerged from the interactions of Native American, European, Caribbean, and African cultures. After emancipation, many slaves left the south and spread the influence of soul food to other parts of the United States. Barbecue is one example of Africaninfluenced cuisine that is still widely popular throughout the United States. The Africans who came to colonial South Carolina from the West Indies brought with them what is today considered signature southern cookery, known as barbacoa, or barbecue. The original barbecue recipe's main ingredient was roasted pig, which was heavily seasoned in red pepper and vinegar. But because of regional differences in livestock availability, pork barbecue became popular in the eastern United States, while beef barbecue became popular in the west of the country.

Other Ethnic Influences.

Cajun and Creole cooking originated from the French and Spanish but were transformed by the influence of African cooks. African chefs brought with them specific skills in using various spices, and introduced okra and native American foodstuffs, such as crawfish, shrimp, oysters, crabs, and pecans, into both Cajun and Creole cuisine. Originally, Cajun meals were bland, and nearly all foods were boiled. Rice was used in Cajun dishes to stretch out meals to feed large families. Today, Cajun cooking tends to be spicier and more robust than Creole. Some popular Cajun dishes include pork-based sausages, jambalayas, gumbos, and coush-coush (a creamed corn dish). The symbol of Cajun cooking is, perhaps, the crawfish, but until the 1960s crawfish were used mainly as bait.

More recently, the immigration of people from the Caribbean and South America has influenced African-American cuisine in the south. New spices, ingredients, combinations, and cooking methods have produced popular dishes such as Jamaican jerk chicken, fried plantains, and bean dishes such as Puerto Rican habichuelas and Brazilian feijoada.

Holidays and Traditions.

African-American meals are deeply rooted in traditions, holidays, and celebrations. For American slaves, after long hours working in the fields the evening meal was a time for families to gather, reflect, tell stories, and visit with loved ones and friends. Today, the Sunday meal after church continues to serve as a prime gathering time for friends and family.

Kwanzaa, which means "first fruits of the harvest," is a holiday observed by more than 18 million people worldwide. Kwanzaa is an African-American celebration that focuses on the traditional African values of family, community responsibility, commerce, and self-improvement. The Kwanzaa Feast, or Karamu, is traditionally held on December 31. This symbolizes the celebration that brings the community together to exchange and to give thanks for their accomplishments during the year. A typical menu includes a black-eyed pea dish, greens, sweet potato pudding, cornbread, fruit cobbler or compote dessert, and many other special family dishes.

Folk beliefs and remedies.

Folk beliefs and remedies have also been passed down through generations, and they can still be observed today. The majority of African-American beliefs surrounding food concern the medicinal uses of various foods. For example, yellow root tea is believed to cure illness and lower blood sugar. The bitter yellow root contains the antihistamine berberine and may cause mild low blood pressure . One of the most popular folk beliefs is that excess blood will travel to the head when one eats large amounts of pork, thereby causing hypertension . However, it is not the fresh pork that should be blamed for this rise in blood pressure, but the salt-cured pork products that are commonly eaten. Today, folk beliefs and remedies are most often held in high regard and practiced by the elder and more traditional members of the population.

Effects of Socioeconomic Status: Poverty and Health

Many of the foods commonly eaten by African Americans, such as greens, yellow vegetables, legumes , beans, and rice, are rich in nutrients . Because of cooking methods and the consumption of meats and baked goods, however, the diet is also typically high in fat and low in fiber, calcium , and

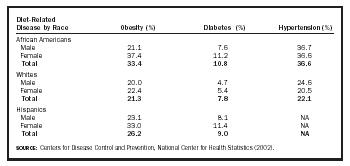

| Diet-Related Disease by Race | Obesity (%) | Diabetes (%) | Hypertension (%) |

| SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2002). | |||

| African Americans | |||

| Male | 21.1 | 7.6 | 36.7 |

| Female | 37.4 | 11.2 | 36.6 |

| Total | 33.4 | 10.8 | 36.6 |

| Whites | |||

| Male | 20.0 | 4.7 | 24.6 |

| Female | 22.4 | 5.4 | 20.5 |

| Total | 21.3 | 7.8 | 22.1 |

| Hispanics | |||

| Male | 23.1 | 8.1 | NA |

| Female | 33.0 | 11.4 | NA |

| Total | 26.2 | 9.0 | NA |

potassium. In 1989, 9.3 million of the black population (30.1%) had incomes below the poverty level. Individuals who are economically disadvantaged may have no choice but to eat what is available at the lowest cost. In comparison to other races, African Americans experience high rates of obesity , hypertension, type II diabetes , and heart disease , which are all associated with an unhealthful diet.

Obesity and hypertension are major causes of heart disease, diabetes , kidney disease, and certain cancers. African Americans experience disproportionately high rates of obesity and hypertension, compared to whites.

High blood pressure and obesity have known links to poor diet and a lack of physical activity. In the United States, the prevalence of high blood pressure in African Americans is among the highest in the world. The alarming rates of increase of obesity and high blood pressure, along with the deaths from diabetes-related complications, heart disease, and kidney failure, have spurred government agencies to take a harder look at these problems. As a result, many U.S. agencies have created national initiatives to improve the diet quality and the overall health of African Americans.

Looking Forward to a Healthier Tomorrow

African-American food and its dietary evolvement since the beginning of American slavery provide a complicated, yet extremely descriptive, picture of the effects of politics, society, and the economy on culture. The deep-rooted dietary habits and economic issues that continue to affect African Americans present great challenges regarding changing behaviors and lowering disease risk. In January 2000, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010, a comprehensive, nationwide health promotion and disease prevention agenda. The overarching goal of this program is to increase quality and years of healthy life and eliminate health disparities between whites and minority populations, specifically African Americans. As national health initiatives and programs continue to improve and target African Americans and other populations in need, preventable diseases will be lowered, creating a healthier U.S. society.

M. Cristina F. Garces Lisa A. Sutherland

Bibliography

Basiotis, P. P.; Lino, M; and Anand, R. S. (1999). "Report Card on the Diet Quality of African Americans." Family Economics and Nutrition Review 11:61–63.

de Wet, J. M. J. (2000). "Sorghum." In The Cambridge World History of Food, Vol. 1, ed. Kenneth F. Fiple and Kriemhil Conee Ornelas. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dirks, R. T., and Duran, N. (2000). "African American Dietary Patterns at the Beginning of the 20th Century." Journal of Nutrition 131(7):1881–1889.

Foner, Eric, and Garraty, John A., eds. (1991). The Reader's Companion to American History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Genovese, Eugene D. (1974). Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage.

Harris, Jessica (1995). A Kwanzaa Keepsake: Celebrating the Holiday with New Traditions and Feasts. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Harris, Jessica (1999). Iron Pots and Wooden Spoons: Africa's Gift to the New World Cooking. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kittler, Pamela Goyan, and Sucher, Kathryn, eds. (1989). "Black Americans." In Food and Culture in America. New York: Van Nostrand and Reinhold.

Popkin, B. M.; Siega-Riz, A. M.; and Haines, P. S. (1996). "A Comparison of Dietary Trends among Racial and Socioeconomic Groups in the United States." New England Journal of Medicine 335:716–720.

Thompson, Becky W. (1994). A Hunger So Wide and So Deep: American Women Speak Out on Eating Problems. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wilson, C. R., and Ferris, W. (1989). The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Witt, Doris (1999). Black Hunger. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zinn, Howard (1980). "Drawing the Color Line." In A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins.

Internet Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2002). "Monitoring the Nation's Health." Available from <http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/>

U.S. Census Bureau (2001). "General Demographic Characteristics for the Black or African American Population." Available from <http://www.census.gov>

U.S. Census Bureau (2001). "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics." Available from <http://factfinder.census.gov>

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Available from <http://health.gov/healthypeople>

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: