Heart Disease - Coronary artery disease

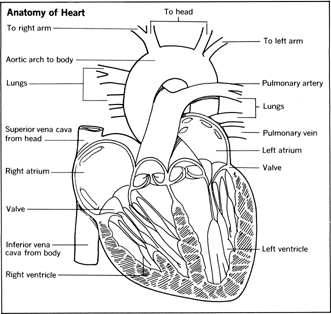

To keep itself going, the heart relies on two pencil-thick main arteries. Branching from the aorta, these vessels deliver freshly oxygenated blood to the right and left sides of the heart. The left artery is usually somewhat larger and divides into two sizable vessels, the circumflex and anterior branches. The latter is sometimes called the artery of sudden death, since a clot near its mouth is common and leads to a serious and often fatal heart attack. These arteries wind around the heart and send out still smaller branches into the heart muscle to supply the needs of all cells. The network of vessels arches down over the heart like a crown—in Latin corona — hence the word coronary .

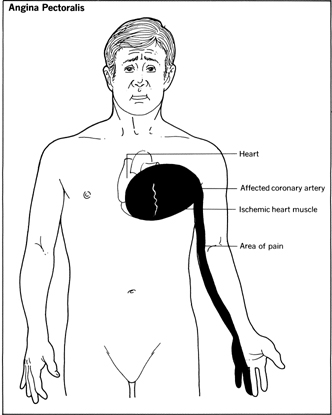

Coronary artery disease is the most frequent cause of death from cardiovascular disease. It is brought on by obstructions (plaque) that develop in the coronary vessels nourishing the heart muscle, a condition termed atherosclerosis . These fatty blockages impair adequate delivery of oxygen-laden blood to the heart muscle cells. The result may be angina pectoris: short episodes of viselike chest pains that strike when the heart fails to get enough blood; or it may be a fullblown attack, where blood-starved heart tissue dies.

Heart attacks strike about 1.6 million annually, killing about 600,000. Overall, more than six million adults either definitely have or are suspected of having some degree of coronary disease; for this reason it has been labeled the “twentieth-century epidemic”.

Risk Factors of Coronary Artery Disease

- 1. Sedentary lifestyle

- 2. High cholesterol

- 3. High blood pressure

- 4. Obesity

- 5. Cigarette Smoking

- 6. Diabetes

- 7. Family History of Coronary Artery Disease

Controlling the Risk Factors of Coronary Artery Disease

- • Exercise regularly. Consult your physician for the best program for your age and physical condition.

- • Eat less saturated fat and cholesterol. Substitute polyunsaturated vegetable fats or monounsaturated fats. Eat more poultry, fish, and complex carbohydrates.

- • Undergo periodic tests of your total cholesterol level. A total cholesterol reading under 200 is desirable; a reading from 200 to 239 ranks as “borderline high” and indicates the need for dietary adjustments; levels above 240 are considered “abnormal” and indicate a need to consult a physician and possibly undergo drug therapy.

- • Control high blood pressure. Those whose blood pressure is consistently 140/90 or higher are considered to have high blood pressure. There is some evidence that hypertension in women should be treated differently from that in men.

- • Don't smoke. The heart attack death rate is 50 to 200 percent higher, depending on age and number of cigarettes consumed, among men who smoke as compared with nonsmokers. Giving up the habit can decrease the coronary risk to that of the nonsmokers within two years; the danger of smoking is reversible.

- • Get down to your proper weight and stay there. Excess weight taxes the heart, making it work harder.

- • An aspirin every other day has been shown to lessen the chance of having a heart attack for men at risk. Because aspirin decreases the clotting ability of the blood, it should not be taken by those with high blood pressure, a family history of stroke, bleeding disorders, ulcers, or impaired liver of kidney function. You should consult your physician before taking aspirin regularly.

Atherosclerosis

Coronary artery disease exists when flow of blood is impaired because of narrowed and obstructed coronary arteries. In virtually all cases, this blockade is the result of atherosclerosis, a form of arteriosclerosis , the thickening and hardening of the arteries. Atherosclerosis , from the Greek for porridge or mush, refers to the process by which fat carried in the bloodstream piles up on the inner wall of the arteries like rust in a pipe. As more and more fatty substances, including cholesterol, accumulate, the once smooth wall gets thicker, rougher, and harder, and the blood passageway becomes narrower.

This fatty clogging goes on imperceptibly, a process that often begins early in life. To some extent, the body protects itself by developing, over a long period of time, alternative arterial connections, termed collateral circulation , through which the blood flow bypasses the diseased arteries. Eventually, however, blood flow may be obstructed sufficiently to cause the heart muscle cells to send out distress signals. The brief, episodic chest pains of angina pectoris announce that these cells are starving and suffering for lack of blood and oxygen. Flow may be so severely diminished or totally plugged up that a region of the heart muscle dies. The heart has been damaged; the person has had a heart attack.

The preventive measures for atherosclerosis are the same as those for a heart attack: exercise regularly, cut down on cholesterol and fat, don't smoke, control high blood pressure, and keep weight down. Avoiding these risk factors greatly decreases the chance of developing serious atherosclerosis.

Angina

Angina pectoris means chest pain (from the Latin angere meaning choke and pectoralis meaning chest). Angina occurs when the heart is called upon to pump more blood to meet the body's stepped-up needs. To do so means working harder and faster. If one or more of the heart's supply lines is narrowed by disease, the extra blood and oxygen required to fuel the pump cannot get through to a region of the heart muscle. Anginal pain is a signal that muscle cells are being strained by an insufficiency of oxygen; they are, as it were, gasping for air.

The attacks usually are brief, lasting only a matter of minutes. Attacks stop when the person rests. Some people apparently can walk through an attack, as if the heart has gotten a second wind, and the pain subsides.

Symptoms

Angina attacks are likely to appear when sudden strenuous demands are placed on the heart. They may come from physical exertion—walking uphill, running, sexual activity, or the effort involved in eating and digesting a heavy meal. Watching an exciting movie or sporting event can trigger it; so might cold weather. An attack can occur even when the individual is lying still or asleep—perhaps the result of tension or dreams. The most obvious characteristic of an angina attack is pain.

Usually the pain is distinctive and feels like a vest being drawn too tightly across the chest. Sometimes it eludes easy identification. As a rule, however, the discomfort is felt behind the breastbone, occasionally spreading to the arms, shoulders, neck, and jaw. Not all chest pain indicates angina; in most cases it may simply be gas in the stomach.

Treatment

It is important to note that angina is a symptom, not a disorder. In most cases it is the result of atherosclerosis, and thus the program recommended for reducing the risk of atherosclerosis also applies to angina. In addition, treatment may involve merely rearranging activity to avoid overly taxing physical labors or emotional situations likely to induce discomfort. A major medication used for angina is nitroglycerin . It dilates small coronary blood vessels, allowing more blood to get through. Nitroglycerine pellets are not swallowed but are placed under the tongue, where they are quickly absorbed by blood vessels there and sped to the heart; discomfort passes in minutes. Nitroglycerin is also available in a sprayable form. Often anginal attacks can be headed off by taking the tablets or spray before activities likely to bring on an attack. Some people experience temporary, mild headaches as a side effect of taking nitroglycerin.

Still other drugs have been found to relieve angina pains. One group, called the beta-blockers, slows down the heart's action and thus its need for oxygen. Widely used to treat high blood pressure as well as heart disease, the beta-blockers may cause shortness of breath. For that reason, physicians usually prescribe other medications for persons with asthma.

The first of the beta-blockers to come into use was propranolol . But at least five chemically related drugs may be prescribed: atenolol, timolol, metoprolol, nadolol, and pindalol. Physicians generally try to fit one of these drugs to the problems of the individual patient. There is some evidence that propranolol and nitroglycerin taken together may increase the effectiveness of therapy.

A second group of drugs for angina is known as the calcium slow channel blockers, or simply calcium channel blockers. These drugs prevent coronary spasms, one cause of angina chest pains, by blocking the flow of calcium ions to the heart and thus dilating the arteries and increasing blood flow to the heart. The heart's demand for oxygen is lessened, and blood pressure is lowered. Three chemically different calcium channel blockers in use are verapamil, nifedipine, and diltiazem.

Angina does not mean a heart attack is inevitable. Many angina patients never have one, whether the result of collateral circulation, treatment with medication, or lifestyle changes. Should attacks of angina begin to worsen in spite of these, however, angioplasty or coronary bypass surgery may be necessary.

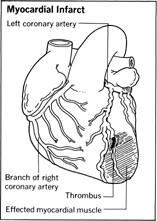

Heart Attack

Heart attack is the common term for myocardial infarction , or death of heart muscle, which is also described as coronary occlusion (total closure of the coronary artery) or coronary thrombosis (formation of a blood clot, which closes the artery).

Although heart attacks can occur at any age, the frequency of heart attacks begins to build rapidly between the ages of 30 and 44. In this age group, men experience heart attacks about 4 times as often as do women. However, beginning at about age 45—the average age of menopause—the rate among women begins to climb rapidly. By the age of 65, women are about as likely as men to experience heart attacks. The overall number of people who die from heart attacks in the United States annually is roughly 500,000.

Symptoms

Sometimes heart attacks are so vague or indistinct that the victim may not know he has had one. Often a routine electrocardiogram turns up an abnormality indicative of an infarct , or injured area, thus the importance of periodic checkups. Special blood tests can also detect an elevation in the number of white blood cells or a rise in the enzyme content, resulting from leakage when heart muscle cells are injured. Most heart attacks, however, do not sneak by. There are well-recognized symptoms. The most common are:

- • A feeling of strangulation, crushing, or compressing

- • A prolonged, oppressive pain or unusual discomfort in the center of the chest that may radiate to the left shoulder and down the left arm or up the neck into the jaw

- • Abnormal perspiring

- • Sudden, intense shortness of breath

- • Nausea or vomiting (because of these symptoms, an attack is sometimes taken for indigestion; usually, coronary pains are more severe)

- • Occasionally, fainting

Treatment

Knowing these warning signals and taking proper steps may make the difference between life and death. Call a physician or get to a hospital as soon as possible. Time is crucial. Most deaths occur in the initial hours after attack. About 40 percent, for example, die within one hour after onset of a major heart attack.

Often, death is not due to any widespread damage to the heart muscle, but rather to a disruption in the electric spark initiating heart muscle contraction—the same spark measured by the electrocardiogram. These out-of-kilter rhythms, including complete heart stoppage or cardiac arrest, are often reversible with prompt treatment.

For patients whose heart attack is the result of a blood clot (thrombus) the administration of thrombolytic drugs, which dissolve the clot and thus limit the extent of damage to the heart, increase the survival rate by 50 percent. Other drugs used to treat the heart include antiarrhythmics, which restore a regular beat to an irregularly beating heart, and vasopressors or inotropic agents that stimulate the heart and enhance heart function. Among the many cardiostimulants, or inotropic drugs, is a large group called partial beta 1 agonists that accelerate the rehabilitation process and increase exercise tolerance.

Of two other classes of therapeutic drugs, calcium and beta channel blockers are used to slow the heart rate, while angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors increase blood flow to the kidneys. The ACE inhibitors also block an enzyme that raises blood pressure. Among the diuretics are Dyazide and furosemide, marketed as Lasix. Both help to prevent fluid accumulation in the lungs.

Because most heart attacks are the result of reduced blood flow due to clots or buildup of deposits on arterial walls, following a heart attack the problem arteries must be identified. This is done in a procedure called coronary arteriography (cardiac catheterization), where blocked arteries are identified by X-ray “movies” taken of an injected opaque dye. Another technique, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), uses magnetic forces to identify problems in specific areas of the heart and its arteries.

Once clogged arteries are identified, they must be cleared. The procedures that clear arterial blockages begin with the pushing of a catheter through an artery in the leg or arm and into a coronary artery that has been narrowed by the buildup of cholesterol, minerals, cell debris, and other material (plaque), which cuts off the flow of blood.

In one common procedure, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty , or balloon angioplasty, a balloon attached to a catheter is maneuvered to the site of arterial blockage and then inflated. The inflation forces open the artery by crushing the plaque against the arterial walls, compressing but not removing it. The balloon and catheter are then removed.

Another procedure, atherectomy, removes the blockage rather than just flattening it. After one catheter is guided through the artery to the obstruction, a second catheter—equipped with a cutting tool—is guided through the first. The tool is then used to remove the blockage.

In about a third of the cases treated using these techniques the plaque returns within six months. One solution to this problem, called restenosis, is the use of a stent—a small, tubular structure. After an angioplasty or atherectomy, a catheter is used to guide the stent into place at the site of the blockage. Lattice-like in structure, the stent can be expanded to press against the arterial wall once it is in place. It remains there permanently, keeping the artery open.

In cases where the blocked section of the artery is too long or difficult to reach, coronary artery bypass surgery must be performed.

Coronary Care Units

Special hospital centers called coronary care units (CCUs) have been created to provide for heart attack victims. Headed by a cardiologist and staffed by highly trained nurses, the CCU provides around-the-clock electronic devices that keep watch over each patient's vital functions, particularly the heart's electrical activity. The critical period is the first 72 hours, when up to 90 percent of heart attack patients experience some type of electrical disturbance or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

Patient rooms in the CCU are designed to ensure privacy and a tranquil, cheerful environment. Rooms may be separated from one another by curtains or partial or full walls.

Each patient is connected via electrodes attached to the skin to a heart monitor, which records the rhythm and rate of the heartbeat and the blood pressure. An alarm system notifies the nurse when a major change is taking place in the patient's condition.

Other CCU equipment includes defibrillators for treatment of the condition called ventricular fibrillation (see section on arrhythmias), electroshock equipment, intravenous pacemakers, and a crash cart stocked with such items as the drugs needed for emergency cardiac care (ECC) and endotracheal tubes.

Where in use, these units have reduced heart attack deaths among hospitalized patients up to 30 percent. If all heart victims surviving at least a few hours received such care, more than 50,000 lives could be saved annually.

Emergency Care

Most heart attack victims never reach the hospital. About one-third die before they receive medical care. Many of these deaths result from ventricular fibrillation or cardiac arrest—reversible disturbances when treated immediately. These considerations led to the concept of mobile coronary care units which have become common in U.S. communities, successfully reducing mortality.

An emergency technique called cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has also reduced out-of-hospital heart attack mortality figures. Used in conjunction with mouth-to-mouth breathing, CPR is an emergency procedure for treating cardiac arrest. The lower part of the breastbone is compressed rhythmically to keep oxygenated blood flowing to the brain until appropriate medical treatment can be applied to restore normal heart action; often cardiac massage alone is enough to restart the heart. Training for the technique is widely available at hospitals or local branches of the Red Cross. Regular refresher courses are important, however, because improper use of the technique could fracture a rib or rupture a weakened heart muscle if too much pressure is applied.

Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery

Coronary artery bypass surgery involves removing a short length of vein from the leg and using it to reroute blood flow in the heart around severely blocked arteries. One to nine segments of these arteries may receive bypasses, although four to five is the most common.

Instead of a leg vein, it is often preferable to use either of the two (or both) internal mammary arteries for the bypass. (One common problem with using a leg vein is the tendency to develop blockages similar to those in the arteries it was intended to bypass; the mammary arteries are more resistant to the build up of atherosclerosis.

Although coronary artery bypass surgery relieves the debilitating angina or reduces the risk from severely blocked arteries by restoring adequate blood flow to the heart, it does not cure the underlying disease—atherosclerosis. Thus to reduce the risk of further complications or the need for another bypass operation, the patient must take care to follow the recommended dietary and lifestyle changes for reducing atherosclerosis.

Heart Surgery

Direct surgery on the heart is possible because of the development of the heart-lung machine, which takes over the job of oxygenating and pumping blood into circulation, thus giving surgeons time to work directly on a relatively bloodless heart.

Heart surgery is performed to correct congenital defects (see section on congenital heart disease), problems associated with coronary artery disease, hypertension, rheumatic fever, and congestive heart failure (see these sections), and injuries or diseases of the heart. Heart valves and arteries may be repaired or replaced, or the heart itself may be replaced.

The major valves of the heart—mitral, aortic, pulmonary, and tricuspid—may all become either obstructed (thus restricting the blood flow), a condition called stenosis, or they may fail to close properly (causing backflow of blood), a condition called regurgitation .

Stenosis may be corrected by a valvotomy, which enlarges the constricted valve opening. Some cases of valve regurgitation can be repaired surgically, others require the replacement of the valve.

Heart transplant may be required when such diseases of the heart as cardiomyopathy (heart muscle disease), myocarditis (inflammation of the myocardium), and pericarditis (inflammation of the sac surrounding the heart) do not respond to lifestyle changes or medication.

Heart transplantation has been performed with increasing success for more than 20 years. The best candidates for transplantation are psychologically stable, otherwise healthy individuals under 60. About 80 percent of transplant patients survive for at least a year. Some have lived for more than a decade.

Two problems associated with heart transplantation are the acquisition and storing of donor hearts and overcoming the body's rejection response to transplants. The former means a long waiting list for potential transplant patients. Controlling the latter is becoming increasingly more successful with immunosuppressive drugs. For more information, see “Heart Surgery” in Ch. 20, Surgery . See also “Organ Transplants” in Ch. 20, Surgery .

Recuperation

Beyond the 72-hour crisis period, the patient will still require hospitalization for three to six weeks to give the heart time to heal. During the first two weeks or so, the patient is made to remain completely at rest. In this period, the dead muscle cells are being cleared away and gradually replaced by scar tissue. Until this happens, the damaged area represents a dangerous weak spot. By the end of the second week, the patient may be allowed to sit in a chair and then to walk about the room. Recently, some physicians have been experimenting with getting patients up and about earlier, sometimes within a few days after their attack. Although most patients are well enough to be discharged after three or four weeks, not everyone mends at the same rate, which is why physicians hesitate to predict exactly when the patient will be released or when he will be well enough to resume normal activity.

About 15 percent of in-hospital heart attack deaths come in the post-acute phase owing to an aneurysm , or ballooning-out, of the area where the left ventricle is healing. This is most likely to develop before the scar has toughened enough to withstand blood pressures generated by the heart's contractions. The aneurysm may kill either by rupturing the artery or by so impairing pumping efficiency that the heart fails and the circulation deteriorates.

Most heart attack patients are able to return to their precoronary jobs eventually. Some, left with anginal pain, may have to make adjustments in their jobs and living habits. What kind of activity the patient can ultimately resume is an individual matter to be worked out by the patient with his physician. The prescription usually involves keeping weight down and avoiding undue emotional stress or physical exertion; moderate exercise along with plenty of rest is encouraged.

Before or after a heart attack victim returns to work and more normal life habits, physicians may want to know how he or she will react to stresses, medicines, and other factors and conditions. This is done by using “ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring”—a portable EKG—which delivers electrocardiographic readings for 6 to 24 hours or longer while the patient goes about his normal activities. Electrodes are attached to the patient's chest over the heart. The electrodes connect with a tape recorder that makes electrocardiograms. Completely portable because of its weight—less than two pounds—the tape recorder/monitor is carried on a strap hung over the patient's shoulder or is attached to the wearer's belt.

The monitor's recordings are especially useful in diagnosing arrhythmias, which may occur at unpredictable times. Patients using the ambulatory monitor are generally asked to supplement the cardiographic record by keeping notes on their activities. These notes show the physician the activities in which the patient was engaged from hour to hour during the day. The notes may be matched up with the EKG to show what stresses accompanied particular activities. Some monitors have a special band on which the patient can record oral reports of his activities. The monitor's tape record and the patient's written or dictated notes help the physician give more specific instructions to the patient regarding his activities to facilitate recovery.

Arrhythmias

A disturbance in the rhythm of the heart is termed arrhythmia and can range from a mild “skipped beat” to a life-threatening failure to pump. The latter is called ventricular fibrillation and is usually associated with heart disease or occurs soon after a heart attack. The phenomenon of cardiac arrest (sudden death) is most often caused by ventricular fibrillation and is the leading cause of death in young and middle-aged men.

In ventricular fibrillation, the lower chambers of the heart contract in an uncoordinated and inefficient manner, causing blood-pumping to cease completely. The patient may experience palpitations, lightheadedness, chest discomfort, shortness of breath, or loss of consciousness. Treated within one minute, the patient has a 90 percent or better chance of surviving. A delay of three minutes means a survival rate of less than 10 percent because of extensive and irreversible brain and heart damage.

Treatment involves the use of an instrument called a defibrillator . Through plates applied to the chest, the device sends a massive jolt of electricity into the heart muscle to get the heart back on the right tempo.

More significantly, it is now also possible to head off ventricular fibrillation, so that the already compromised heart will not have to tolerate even brief episodes of the arrhythmia. Ventricular fibrillation is invariably heralded by an earlier, identifiable disturbance in the heartbeat. Most frequently, the warning signal is a skipped or premature ventricular beat. Picked up by the coronary care monitoring equipment, the signal alerts the unit staff to administer heart-calming medicaments that can ward off the danger. One such drug is lidocaine , a long-used dental anesthetic found to have the power to restore an irritated heart to electrical tranquility.

Less serious arrhythmias than ventricular fibrillation include atrial flutter (where the atria contract too often), atrial fibrillation (where they contract in an ineffective and uncoordinated manner), and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (where the heart rate may race at between 140 and 240 beats per minute for minutes or even days).

Most all conditions of arrhythmia are associated with heart disease or heart attacks and can be controlled with lifestyle changes and medications designed to pace the heart. Others are caused by a malfunctioning mitral valve of the heart or the sinus node (the area of the heart that sends electrical signals to the chambers, controlling the beat; i.e., the heart's pacemaker).

Ten years ago this past October of 2001 I was diagnosed with having Artery Desease at the age of 41. The heart doctor ended up doing a double by-pass taking the artery from both leg and chest but ended up using the one in the chest which I understand is small. I had a very hard time recouping from this surgery. I had to have blood transfusions, plus fluid by 4 and 5 liters were being drained out of my lungs at least twice a week. Through it all the good news was that my heart was not damaged.

Three years after the surgery, I started having problems again. Another Leg Cather was done and I was told that the new artery was already blocked up 25%. The pain has gotten to a point to where it never goes away and at times it's so uncontrolable that I can only pray for mercy.

Last month that went back in and did another Cather since the one done 7 years ago. I was having a good day that day with no pain or problems. The doctor told me that the bypass had died and had rotted in my heart. He said that he has read that this could happen in books but has never seen a case but that my heart had found it's own way of by-passing another way on it's own. I have to say that I felt blessed hearing this for I felt a miracle had happened.

But since I've got home the pain is increasing more and more. All I can do is take Morphine and lay for hours waiting for the pain to be a little more tolerable. Did they just send me home to die? If my heart has indeed found it's own way of by-passing then I figure I shouldn't be having this pain. The doctor sent me home and told me to go and see my general doctor and have my stomach and lungs and tested.

I know the difference between heart pain and stomach pain and this is not stomach pain. I don't know what to do at this point. It's like nobody is listening to me and don't have any answers for me. I know they have came a long way with the heart but it seems to me that all is not known as they make you believe or how they think. If it's not in a book right in front of their faces that says so, then what's going on with you is impossible or in your mind.

I've been searching online to answers of what happens when a person valve re-routes itself but I cannot seem to find the answers that I'm looking for. If anybody knows can you please lead me to the link.

Many Thanks,