Terrorism, Philosophical and Ideological Origins

█ ERIC v.d. LUFT

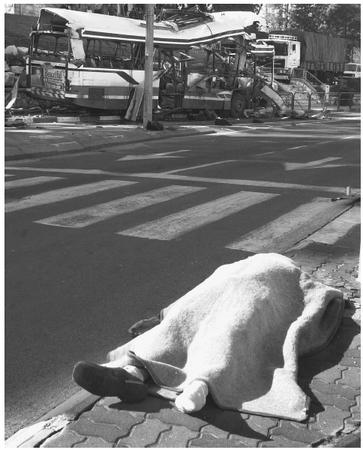

Terrorism is the systematic belief in the political, religious, or ideological efficacy of producing fear by attacking—or threatening to attack—unsuspecting or defenseless populations, usually civilians, and usually by surprise. Terrorist attacks are desperate acts of those who feel themselves to be otherwise powerless. Terrorism is self-righteous, absolutist, and exclusivist. In general, terrorist policy adherents are unwilling or unable to negotiate with their perceived enemies, or prevented by political, social, or economic circumstances from doing so. The philosophical underpinnings of terrorism have become well established worldwide.

The terms "terrorism" and "terrorist" came into the language in the 1790s when British journalists, politicians, orators, and historians used them to describe the Jacobins and other particularly violent French revolutionaries. The terms have evolved since then, and now typically refer to furtive acts by unknown, underground perpetrators, not overt acts by people in power. Nevertheless, some terrorists are secretly harbored, underwritten, trained, or commanded by states that have vested interests against the terrorists' targets. Examples of state-sponsored terrorism include Afghanistan's support of al-Qaeda in 2001, Libya's involvement in the destruction of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988, and Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) ordering the Reichstag burned down in 1933 so that he could blame the Communists.

Terrorism as we now understand it was not possible until the invention of gunpowder and subsequent explosives and incendiaries. Before that, small cadres of insignificant conspirators generally lacked the means to achieve sudden massive destruction by stealth. Gunpowder enabled weaklings to outmatch and regularly defeat strong warriors for the first time in history. In a historical sense, modern terrorism began with the unrealized November 5, 1605 "Gunpowder Plot" of Guy Fawkes (1570–1606), who, had he lived in the twelfth century, could not have threatened king and parliament as he did in the seventeenth. But even with the ever-widening proliferation and availability of explosives since then, acts of terrorism remained rare until the middle of the nineteenth century, when anarchism arose as an ideological force.

The systematic theory of modern political terrorism arose in Germany during the Vormä , i.e., the time between the accession of Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV (1795–1861) in 1840 and the revolutions of 1848. Edgar Bauer (1820–1886) and Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876), two of the three principal anarchists in the "Young Hegelians," were among terrorism's earliest ideological proponents. The Young Hegelians were a loosely organized group of radical intellectuals influenced to various degrees by the dialectical logic of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1771–1830), the dominant German philosopher of the first half of the nineteenth century. Hegel could not have foreseen that his thought would be perverted in this way and would not have approved of terrorism in any form.

Almost every ideology that became important in the twentieth century arose from the Young Hegelians. These second-generation disciples of Hegel ramified his allegedly self-unifying thought into many disparate movements: socialism and communism came from Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), socialism and Zionism from Moses Hess (1812–1875), secular humanism from Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872), the "higher criticism" of sacred texts from David Friedrich Strauss (1808–1874) and Bruno Bauer (1809–1882), dialectical historicism from August von Cieszkowski (1814–1894), political liberalism from Arnold Ruge (1802–1880), existentialism and anthropological materialism from Karl Schmidt (1819–1864), individualistic anarchism from Max Stirner (1806–1856), utopian anarchism from Bakunin, and raw anarchism and political terrorism from Edgar Bauer.

In chronological order of their earliest terrorist writings, the first six major theorists of terrorism were Edgar Bauer, Bakunin, Wilhelm Weitling (1808–1871), Karl Heinzen (1809–1880), Sergei Nechaev (1847–1882), and Johann Most (1846–1906).

Edgar Bauer became involved with radical groups in 1839 while a student at the University of Berlin. By 1842 both he and his close friend Engels were members of "The Free Ones" ( Die Freien ), the most notorious club of intellectual agitators in Germany in the early 1840s. His first book, Bruno Bauer and his Enemies (1842), defended his brother against government persecution, urged violence, and threatened the Prussian regime with a return to the French Revolution. His 1843 polemic, Critique's Struggle with Church and State , advocated terrorism even more blatantly and earned him a prison sentence.

Bakunin, a Russian noble by birth, studied Hegelianism in Russia from 1836 to 1840 and in Berlin from 1841 to

1842. In October 1842, under the pseudonym Jules Elysard, he published "Reaction in Germany," a revolutionary article in Ruge's Deutsche Jahrbücher . This essay recommended insurgent violence with lines such as: "The urge to destroy is also a creative urge." Bakunin soon distanced himself from Young Hegelianism, but retained his mutinous attitude toward church and state. His extreme anarchism and nihilism were best expressed in God and the State , written in 1871 but published posthumously in 1882.

Weitling was a German tailor who became politically active in 1843. He wrote letters, broadsides, tracts, pamphlets, and books inciting the proletariat to all sorts of violent crimes to free themselves from their oppressors. Even firebrands among the communist, socialist, anarcharist, or syndicalist movements who advocated guerrilla tactics to achieve their political goals were appalled by Weitling's 1843 suggestion that revolutionaries could use arson, theft, and murder to their advantage.

Heinzen is sometimes regarded as the ideological father of modern terrorism, despite the prior writings of Edgar Bauer, Bakunin, and Weitling. Heinzen wrote in 1848 and published in 1849 a powerful essay, "Murder," which claimed that not only the assassinations of leaders, but even the mass murders of innocent civilians, could be effective political tools and should be used without regret. He fled Germany in 1849 and immigrated to America as a "48er," a refugee from the 1848 revolutions. He edited German-language newspapers, notably Der Pionier , in several American cities. Although he never specifically recanted his terrorist beliefs, he became a relatively peaceful socialist. He and his wife lived the last twenty years of his life in Roxbury, Massachusetts, as tenants and friends of a prominent early woman physician, Marie Zakrzewska (1829–1902), one of Der Pionier 's most ardent supporters.

Nechaev, the son of a former Russian serf, learned early to hate government in general and the czarist regime in particular. As a student at the University of St. Petersburg in 1868, his radical agitations soon forced him into exile. He met Bakunin in Geneva, Switzerland, in March 1869, and became briefly his disciple. They co-wrote several inflammatory pamphlets, including The Revolutionist's Catechism (1869), an unrestrained exhortation to anti-government violence, urging relentless cruelty toward all enemies of the revolution and absolute devotion to the cause of destroying the civilized world. Nechaev returned to Russia in August 1869, murdered a political rival named Ivanov in December 1869, and fled back to Geneva. The Swiss extradited him to Russia in 1872. Convicted of murder in 1873 and sentenced to twenty years of hard labor in Siberia, he died in prison under mysterious circumstances. Fedor Dostoevskii (1821–1881) based his character Pyotr Verkhovensky in The Possessed (1871) on Nechaev.

Most was a Social Democrat member of the Reichstag who was forced to flee Germany during Otto von Bismarck's (1815–1898) "Red Scare" of 1878. In exile Most became more radical, relinquished Marxism for anarchism, and edited an inflammatory newspaper, Die Freiheit , first in London, briefly in Switzerland, and after 1882 in America. Embittered after serving eighteen months of hard labor in a British prison and after the German Social Democrat Party expelled him in absentia , his motto became "Long live hate!" He fell in love with dynamite and spent the rest of his career praising it, learning how to use it, and teaching his fellow revolutionaries how to steal it and the money needed to buy it. He probably invented the letter-bomb, though there is no evidence that he ever used one himself. American agents arrested him for sedition in 1901 because Die Freiheit quoted Heinzen's line, "Murder the murderers," the same day that anarchist Leon Czolgosz (1873–1901) killed President William McKinley (1843–1901).

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Breckman, Warren. Marx, the Young Hegelians, and the Origins of Radical Social Theory: Dethroning the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Browning, Gary K. Hegel and the History of Political Philosophy. London: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin's, 1999.

Calvert, Peter. "Terror in the Theory of Revolution," Terrorism, Ideology, and Revolution , edited by Noel O'Sullivan. Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1986.

Confronting Fear: A History of Terrorism , edited by Isaac Cronin. New York: Thunder's Mouth, 2002.

Laqueur, Walter. A History of Terrorism. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 2002.

Luft, Eric v.d. "Edgar Bauer and the Origins of the Theory of Terrorism," The Left-Hegelians: New Philosophical and Political Perspectives , edited by Douglas Moggach and Andrew Chitty. Albany: SUNY Press, forthcoming.

Mah, Harold. The End of Philosophy, the Origin of "Ideology": Karl Marx and the Crisis of the Young Hegelians. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The German Ideology , translated by S. Ryazanskaya. Moscow: Progress, 1964.

——. The Holy Family, or, Critique of Critical Critique , translated by R. Dixon. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1956.

Nomad, Max. Apostles of Revolution. Boston: Little, Brown, 1939.

Origins of Terrorism: Psychologies, Ideologies, Theologies, States of Mind , edited by Walter Reich. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Stirner, Max. The Ego and His Own , translated by Steven Byington, revised and edited by David Leopold. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

The Terrorism Reader , edited by David Whittaker. London: Routledge, 2001.

Wittke, Carl Frederick. The Utopian Communist: A Biography of Wilhelm Weitling, Nineteenth-Century Reformer. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1950.

SEE ALSO

Terrorism, Intelligence Based Threat and Risk Assessments

Terrorist and Para-State Organizations

Terrorist Organization List, United States

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: