Persian Gulf War

█ JUDSON KNIGHT

The Persian Gulf War, in which a coalition led by the United States drove Iraqi forces out of Kuwait in early 1991, was one of the most successful campaigns in history. At a cost of less than 300 Allied lives, coalition troops, whose military actions were largely funded by Saudi Arabia, drove out Saddam Hussein's forces. Thousands of Iraqi lives were lost in the process, however. In their victory, the coalition depended in large part on advances in military technology by the United States, whose arsenal included tools ranging from the F-117A stealth fighter to the M1A1 Abrams tank, and from the Global Positioning System (GPS) to unmanned drones and Patriot missiles. Less clearly successful was U.S. intelligence, which had failed to predict the war. Equally questionable was the ultimate outcome of the war, whose scores would not fully be settled until 12 years later.

The Persian Gulf War is sometimes called simply the Gulf War or Operation Desert Storm, after the U.S.-led campaign that comprised the bulk of the fighting. It may ultimately come to be known as "Gulf War II," or "Persian Gulf War II," with the 2003 operation in Iraq becoming the third in this series. The first, also known as the Iran-Iraq War, lasted from 1980 to 1988, and pitted the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein against the Islamic theocracy in Iran.

Both regimes had taken power in 1979, but the conflict concerned long standing disputes involving lands on the borders between the two nations. In the ensuing hostilities, most nations—including much of the Arab world, the United States, western Europe, and the Soviet bloc—supported Iraq, generally regarded as the lesser of two evils. (Both the Americans and the Soviets also gave covert support to the Iranians as well.) The war, which cost some 850,000 lives, resulted in a stalemate, and both nations built monuments to their alleged victories.

In the aftermath of the first Gulf War, analysts working for the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) prepared a report on the likelihood of Iraqi aggression in the near future. According to the now-infamous study, Saddam had so overextended his resources in the war with Iran that he would not take any major aggressive action for at least three years. In this instance, the CIA underestimated Saddam's penchant for military adventurism.

Invasion and Buildup

On August 2, 1990, without advance warning, Iraqi tanks and troops rolled into neighboring Kuwait. Both nations possessed considerable oil wealth, but Kuwait was by far the richer of the two, and Iraq—particularly under Saddam's regime—had long had designs on Kuwait. Given the importance of oil from the Persian Gulf region, which at that time fueled a great part of the world, neither the United States nor the United Nations (UN) Security Council was inclined to ignore Hussien's aggressive action.

The Security Council on August 3 called for an Iraqi withdrawal, and on August 6 it imposed a worldwide ban on trade with Iraq. On August 5, President George H. W. Bush declared that the invasion "will not stand," and a day later, King Fahd of Saudi Arabia met with U.S. Defense Secretary Richard Cheney to request military assistance. Saudi Arabia, Japan, and other wealthy allies would underwrite most of the $60 billion associated with the resulting military effort. By August 8, U.S. Air Force fighters were in Saudi Arabia.

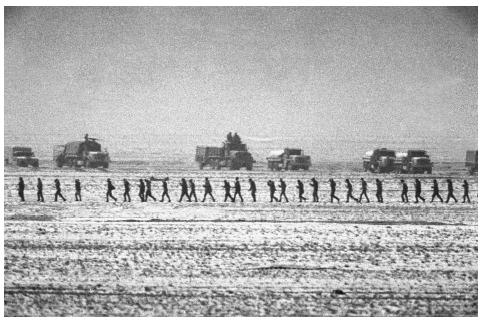

Numerous countries were involved in the military buildup during late 1990, a program known as Operation Desert Shield. By January 1991, the United States alone had some 540,000 troops, along with another 160,000 from the United Kingdom, France, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Kuwait, and other nations. On November 29, 1990, the Security Council authorized use of force against Iraq unless it withdrew its troops by January 15. Saddam's only response was to continue building his troop strength in Kuwait, such that by the time the Allies counterattacked, he had some 300,000 men on the ground.

On January 17, 1991, Operation Desert Shield became Operation Desert Storm, which consisted largely of bombing campaigns against Iraq's command and control, infrastructure, and military assets. In retaliation, Iraq attacked Israel with Scud missiles on January 18. A great portion of the Allied losses occurred in this initial phase, when the Iraqis shot down several low-flying U.S. and British planes.

After thus severing the tail of the invading force, the Allies in February began concentrating on Iraqi positions in Kuwait. Having initially planned an amphibious landing, Allied commander General H. Norman Schwarzkopf instead opted for an armored assault. On February 24, in a campaign phase named Operation Desert Sabre, Allied troops moved northward from Saudi Arabia and into Kuwait. By February 27, they had taken Kuwait City.

At the same time, operations in Iraq itself continued. In the only major bombing run on the capital city of Baghdad, Stealth fighters struck Iraqi intelligence headquarters, while U.S. Army Special Forces teams inserted themselves deep in Iraq. In the southern part of the country, U.S. tanks pounded Iraqi armored reserve forces, while Allied ground forces neutralized Hussien's "elite"

Republican Guard south of Basra. President Bush declared a cease-fire on February 28.

The war had lasted 42 days, and the principal campaign, the mid-January bombing, took just over 100 hours. Credit for this extraordinary success goes to a number of factors, not least of which was strong leadership. On the military side, there was Schwarzkopf on the ground, and in Washington, General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who served as the principal military spokesman during the war. In this, the first major U.S. action since the end of fighting in Vietnam nearly two decades earlier, the performance of both leaders and troops showed that military capabilities had improved extraordinarily since then.

Among the civilian leaders were Cheney, Secretary of State James Baker, National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, and President Bush. The president, sometimes criticized for a failure to communicate his aims to his subordinates or the public as a whole, was quite clear in his objectives for the Persian Gulf War. On January 15, 1991, Bush sent his principal security advisors a memorandum which outlined four major aims: to force an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait, to restore Kuwait's government, to protect American lives, and to promote stability and security in the Gulf region.

Another factor in the success—and another point of comparison with Vietnam—was the near-unanimous support for the action. Whereas American allies and foes alike questioned the value of the action in Vietnam, virtually no one other than Saddam's regime (along with a handful of antiwar protestors at home) opposed the U.S. effort to liberate an invaded nation. This support was helped rather than hurt by an unprecedented level of television coverage. While Vietnam became known as "the first televised war," TV reporting in the 1960s and 1970s was minimal compared to the round-the-clock reportage offered by cable outlets, most notably the Cable News Network (CNN), in 1990 and 1991.

The U.S. arsenal. While human factors deserve a great deal of credit for the success of Allied operations in the Persian Gulf War, the war would not have been won as efficiently without the technological superiority offered by modern weaponry. Among the tools in the U.S. arsenal were a variety of aircraft, including the AH-64 Apache helicopter, the leading anti-armor attack chopper. Introduced in 1984, the Apache could operate in conditions of darkness or low visibility, and was made to sustain heavy pounding from antiaircraft guns.

The E-3 Sentry AWACS (airborne warning and control system) was a masterpiece of modern technology. Packed with electronics, the aircraft—based on the Boeing 707 and introduced in 1977—was made to identify enemy aircraft, jam enemy radar, guide bombers to their targets, and manage the flow of friendly aircraft. Even more cutting-edge were the Pointer and Pioneer drones, or remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs).

Based on Israeli designs and first used by the United States during the war, the RPVs served as airborne spy platforms. The Pioneer, with a range of about 100 miles (161km) and a flight duration of five hours, could take high-definition pictures from 2,000 feet (610 meters) and transmit them to a processing center. In addition to its video cameras, it was equipped with infrared heat sensors, and provided a wealth of intelligence on everything from enemy troop movements to the recommended path for Tomahawk cruise missiles.

Other aircraft included the B-52 Stratofortress bomber, the F-117A Stealth fighter, and the E-8G JSTARS surveillance aircraft. Among the other notable weapons used in the Persian Gulf War were the M1A1 Abrams tank, the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, the MIM-104 Patriot missile defense system, and the Tomahawk cruise missile. High above the ground was the GPS, whose 24 satellites helped soldiers find their bearings in the desert, and assisted artillery in targeting.

Controversies. More controversial than the role of weapons systems was that of intelligence in the Persian Gulf War. The CIA did not inspire a great deal of confidence, either with its initial estimate of Iraqi intentions or from its August 1996 "Final Report on Intelligence Related to Gulf War Illnesses." In the wake of illnesses that broke out among returning personnel, the CIA sought to investigate the connection between these conditions and Iraqi use of chemical or biological agents. The CIA report found no evidence that Iraq had intentionally used such weapons against the United States, even though Saddam used chemical weapons against rebellious Kurds in the north.

More successful was the performance of Defense Department intelligence and related activities, both on the part of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) and various military intelligence and psychological warfare units. DIA began operations in Iraq long before the war, and regularly gathered intelligence reports that proved invaluable to military leadership. The same was true of military intelligence units, while psychological operations had an immeasurable impact by coercing Iraqis to provide the Allies with intelligence on their forces' activities and capabilities.

In addition to controversies over the success of intelligence, there remained questions concerning the success of the war as a whole. This fact was symbolized by the failure of Bush—who, after the war, had the highest poll numbers of any U.S. President since scientific polling began—to gain reelection in 1992. Ironically, Saddam Hussein, who many U.S. leaders had expected to be toppled in the unrest that followed the war, remained in power despite UN sanctions and the imposition of a no-fly zone over the northern and southern portions of the country. Among the factors cited for Bush's sudden loss of popularity from mid-1991 onward (in addition to an economic slowdown and clever campaigning by challenger William J. Clinton) was his failure to remove Saddam Hussein. However, as Bush rightly noted, such action was not within his mandate from the UN.

In 1993, the CIA uncovered evidence that Saddam Hussein had attempted to assassinate Bush, in response for which U.S. warships fired 23 cruise missiles at Iraqi secret service headquarters. The years that followed saw a lengthy process of UN and U.S. attempts to find weapons of mass destruction thought to be hidden in Iraq continually thwarted by Saddam Hussein. When he evicted UN inspectors in 1998, the United States and United Kingdom launched a four-day bombing campaign, Desert Fox, against Iraq.

Although overt evidence was lacking, some in the U.S. intelligence and defense communities suspected Iraqi ties to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, and after the 2001 destruction of those buildings, President George W. Bush indicated that the attacks had been sponsored or at least abetted by Iraq. In March, 2003, the United States launched Operation Iraqi Freedom, a land invasion of Iraq. Though many putative experts claimed that the campaign would not be as successful as the Persian Gulf War, this one—while much less popular globally—was actually shorter, and achieved something the earlier war did not: the removal of Saddam Hussein from his position of leadership. Assisting the younger Bush were several figures from the Persian Gulf War, including Cheney and Powell, now vice president and secretary of state respectively.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Allen, Thomas B., F. Clinton Berry, and Norman Polmar. War in the Gulf. Kansas City, MO: Andrews & McMeel, 1991.

Atkinson, Rick. Crusade: The Untold Story of the Persian Gulf War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993.

Clancy, Tom, and Fred Franks. Into the Storm: A Study of Command. New York: Putnam, 1997.

Dunnigan, James F., and Austin Bay. From Shield to Storm: High-Tech Weapons, Military Strategy, and Coalition Warfare in the Persian Gulf. New York: W. Morrow, 1992.

Freedman, Lawrence, and Efraim Karsh. The Gulf Conflict, 1990–1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Gordon, Michael R., and Bernard E. Trainor. The Generals' War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf. Boston: Little, Brown, 1995.

Hawley, T. M. Against the Fires of Hell: The Environmental Disaster of the Gulf War. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992.

MacArthur, John R. Second Front: Censorship and Propaganda in the Gulf War. New York: Hill and Wang, 1992.

ELECTRONIC:

Fog of War. WashingtonPost.com. < http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-svr/inatl/longterm/fogofwar/fogofwar.ht > (April 13, 2003).

Frontline: The Gulf War. Public Broadcasting System. < http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/gulf/ > (April 13, 2003).

SEE ALSO

B-52

Bush Administration (1989–1993), United States National

Security Policy

Cruise Missile

F-117A Stealth Fighter

GPS

Information Warfare

Iraqi Freedom, Operation (2003 War Against Iraq)

Iraq, Intelligence and Security Agencies

Iraq War: Prelude to War (The International Debate Over the Use and

Effectiveness of Weapons Inspections.)

J-Stars

Kuwait Oil Fires, Persian Gulf War

Patriot Missile System

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: