KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti, USSR Committee of State Security)

█ K. LEE LERNER

The KGB ( Komitet Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti or Committee of State Security) was the preeminent Soviet intelligence agency and Soviet equivalent of the American CIA. The KGB was the primary organization for intelligence and counterintelligence matters during the later Soviet period. Although the NKVD was tasked with internal security, the KBG role in political security and counterintelligence was so broad that its operations often touched on internal security matters. For example, in 1957, Soviet border guards were placed under KGB supervision.

The KGB and Western intelligence services played a continual deadly game of "cat and mouse" (both as pursuers and the pursued) throughout the Cold War, with some of the most intense activity centered on Berlin (e.g., Operation Gold and the Berlin tunnel episode). In 1967, Yuri Andropov, then head of KGB and later Soviet premier, described the role of the KGB and other state security bodies as "a bitter and stubborn battle on all fronts, economic, political, and ideological."

Origin and formation of the KGB. The first Soviet state security organization, the Cheka (aka, Vecheka or All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-revolution and Sabotage) was created by the new Soviet leaders almost immediately following the November revolution in 1917. In 1922, the State Political Directorate (GPU) succeeded the Cheka and was then placed under the control of the NKVD (People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs).

When the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was formally created the next year, the GPU became the OGPU (Unified State Political Directorate) and was made an independent directorate (disassociated from the NKVD) of the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. In the political infighting and turmoil of the early 1930s in the Soviet Union, the OGPU was renamed the GUGB (Chief Directorate of State Security) and simultaneously placed under the control of the also reformed All-Union NKVD.

This fusion of state security and intelligence functions produced powerful influence embodied in a string of leaders that included G. G. Yagoda, N. I. Yezhov (1936), and Lavrentii Beria (1938).

In 1941, during World War II, the GUGB was split from the NKVD and granted equal status as the NKGB. The first NKGB director, V. N. Merkulov, had worked directly with Beria and followed similar brutal methodologies. The NKGB was tasked with conducting both external espionage and counter-espionage activities as well as guaranteeing Communist Party rule by suppressing counter-revolutionary organizations.

As the Nazi invasion pushed deeper into Russia, the NKGB was once again briefly fused with NKVD under its old title as the GUGB to streamline efforts to coordinate an effective defense against the Nazi forces. As the front stabilized and the Soviets began to push the Germans back, the GUGB was once again given independent status as the NKGB.

Derived from special sections of the NKVD Army (NKO) and Navy (NKVMF), a powerful new element,

SMERSH ( SMERrt SHpionam or "Death to Spies") became a forerunner to KGB assassination teams. In 1940, Leon Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico City by SMERSH. Trotsky had long been a rival of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, who recognized that Trotsy's role in launching the Bolshevik takeover of Russia alongside V. I. Lenin gave him much greater revolutionary legitimacy. SMERSH agents tracked Trotsky for more than a decade before the assassination.

Following World War II, the Soviet government renamed the People's Commissariats as ministries and the NKVD became the MVD and the NKGB became the MGB. In March, 1953, the day after Stalin died, Beria united the MGB and MVD into one organization (retaining the title MVD). After Beri's trial and execution in 1954, espionage activities were assigned to a reconstituted unit designated as the KGB and placed under the direction of the Soviet Council of Ministers. In 1978, the KGB chairman was assured a place on the Soviet Council of Ministers.

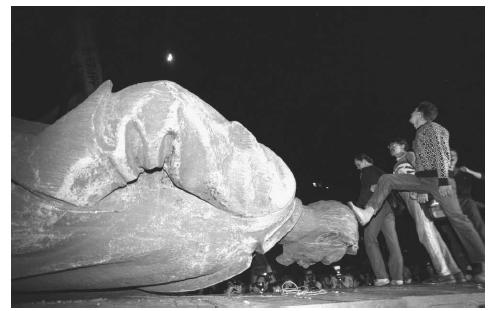

As part of his attempted reforms of the Soviet Union (e.g., glasnost ), the last Soviet premier, Mikhail Gorbachev also attempted to reform the KGB before it was dissolved in 1991 but these attempts were met with resistance within the KGB hierarchy and eventually created tension significant to the collapse of the Soviet Union. The fate of the KGB was sealed when its leader, Colonel General Vladimir Kryuchkov, ordered KGB agents to participate in the failed August, 1991, coup attempt against Mikhail Gorbachev. KGB-directed forces surrounded Gorbachev's Crimean dacha (house) for three tense days before the coup collapsed.

The Soviet Union collapsed and splintered in 1991. The KGB was dissolved and the Federal'naya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti , or Federal Security Service (FSB), Russian Federal Counterintelligence Service (FSK), and Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) were formed (from resources that included some former KGB elements) to serve the intelligence needs of the new Russian Federation.

KGB tactics. KGB operatives were masters at tactics ranging from disinformation (in Russian, dezinformatsiya ) to assassination. As did their Western counterparts, KGB operatives also employed technology specifically designed for espionage operations. KGB agents employed a range of weapons, including exotic devices like poison pens that fired hydrocyanic acid gas or pellets of ricin. Another celebrated example involved the KGB development of the lipstick pistol, or "kiss of death." Created by KGB scientists, the lipstick pistol contained a 4.5-mm single-shot pistol encased in rubber and disguised as a tube of lipstick. The deadly poison ricin came to widespread public attention in 1978, when it was used during the KGB assassination of Bulgarian dissenter Georgi Markov in the United Kingdom. Markov, a BBC broadcaster, died several days after being jabbed by an umbrella at a bridge in London. The poison-tipped umbrella injector was designed by KGB scientists.

KGB operatives used disinformation not only directly against Western governments, but also against governments not following pro-Soviet policies. For example, KGB operatives used disinformation tactics in attempts to destabilize Egyptian president Anwar Sadat for his increasingly pro-Western policies by issuing false statements and writing attributed to Islamist fundamentalists. The disinformation not only contributed to the assassination of Sadat, but also helped fuel Islamist terrorism.

To avoid direct conflict with the U.S., the KGB funded subversive groups and domestic terrorists within the United States (e.g., the Weathermen, a 1960s radical group) through intermediaries such as Cuba.

Spy vs. spy. As did their Western intelligence counterparts, KBG officers continually attempted to recruit agents and plant moles in Western intelligence organizations. The KGB's success in this effort was unparalleled, the most infamous success coming with the compromise of British intelligence by the Cambridge University spy ring and mole Kim Philby.

KGB methods of suppression of moles and traitors could be brutal. According to one eyewitness account, when KGB officers discovered a fellow officer had provided information to the CIA, he was thrown feet first into a roaring furnace while his colleagues watched.

The most well known mole for Western intelligence operating within the KGB was Colonel Oleg Penkovsky. Penkovsky initially served the Soviet regime faithfully, but when he became disillusioned with communism and the Soviet leadership, Penkovsky ultimately offered his services to British intelligence. United States President John F. Kennedy used information provided by Penkovsky during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The KGB subsequently arrested Penkovsky. After being convicted of treason, Penkovsky was executed.

The Legacy of the KGB. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the KGB, access to secret archives and testimony of former KGB officers and agents has exposed several double agents. The extent of the Walker family espionage activities became apparent, and specific sensitive U.S. Navy and National Security Agency documents were discovered in the KGB archives.

In 1994, long-time CIA veteran Aldrich Ames was discovered to be a KGB mole. The information he sold to the KGB included the names of Russian double agents and operatives working for the U.S. within the Soviet intelligence community, ultimately leading to their capture, imprisonment, or execution by Soviet authorities.

In 2001, FBI agent Robert Philip Hanssen was arrested for conspiracy to commit espionage. Hanssen eventually pled guilty to charges that he had spied for the KGB.

Although the predominant sentiment in contemporary Russia is one of relief from fear of the KGB, some express the sentiment that the once omnipresent intelligence-gathering entity was so powerful and invasive that it minimized the commission of ordinary crimes, which now plague Russia.

Some of the bizarre disinformation created by the KGB has become a source of urban legends occasionally regurgitated by ill-informed or profoundly anti-U.S. critics. For example, documents in the KGB archives provide evidence that operatives mounted a disinformation campaign laden with pseudo-scientific "proofs" that the United States had deliberately created the AIDS virus in the laboratory to use as a biological weapon.

The KGB mounted a major disinformation campaign during the Korean War that resulted in lasting influences on North Korean and Western relations. KGB operatives disseminated information that accused U.S.-led United Nations forces of using biological and chemical warfare against North Korean civilians, information that is still propagated by the North Korean government and so continues to poison public opinion against the U.S. and other Western powers.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Bittmann, Ladislav. The KGB and Soviet Disinformation. Washington: Pergamon-Brassey's International Defense Publishers, 1985.

Kessler, Ronald. Moscow Station: How the KGB Penetrated the American Embassy. New York: Scribner's, 1989.

Mitrokhin, Vasily, ed. KGB Lexicon: The Soviet Intelligence Officer's Handbook. London: Frank Cass, 2002.

PERIODICALS:

Gordievsky, Oleg. "The KGB Archives." Intelligence and National Security 6, no. 1 (Jan. 1991): 7–14.

Waller, Michael J. "State within a State: The KGB and its Successors" Perspective IV, no. 4 (1994).

OTHER:

Romerstein, Herbert. "Disinformation as a KGB Weapon in the Cold War." Prepared for a Conference on Germany and Intelligence Organizations: The Last Fifty Years in Review, sponsored by Akademie fur Politische Bildung Tutzing, June 18–20, 1999.

SEE ALSO

Ames (Aldrich H.) Espionage Case

Assassination

Assassination Weapons, Mechanical

Berlin Tunnel

Biochemical Assassination Weapons

Cambridge University Spy Ring

Cameras

Cameras, Miniature

CIA (United States Central Intelligence Agency)

CIA, Formation and History

Cold War (1945-1950), The Start of the Atomic Age

Cold War (1950-1972)

Cold War (1972-1989): The Collapse of the Soviet Union

Concealment Devices

Crime Prevention, Intelligence Agencies

Cuba, Intelligence and Security

Czech Republic, Intelligence and Security

Dirty Tricks

Disinformation

Document Forgery

Double Agents

Hanssen (Robert) Espionage Case

Intelligence Agent

MI5 (British Security Service)

MI6 (British Secret Intelligence Service)

Propaganda, Uses and Psychology

Rosenberg (Ethel and Julius) Espionage Case

Soviet Union (USSR), Intelligence and security

Stasi

Ukraine, Intelligence and Security

Venona

Walker Family Spy Ring

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: