CIA, Formation and History

█ MICHAEL J. O'NEAL

United States military planners had always relied on intelligence during wartime, but it was not until World War II that the U.S. government began collecting intelligence systematically. Even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been having doubts about the effectiveness of the nation's intelligence-gathering efforts because they were scattered among the various branches of the military. To correct this deficiency, he appointed William J. Donovan, a New York lawyer who had won the Congressional Medal of Honor as an Army colonel in World War I, to put together a plan for an intelligence service. Out of Donovan's plan emerged the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)

in June 1942. The OSS, under Donovan's leadership, was given the task of collecting and analyzing information needed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the heads of all the branches of the nation's military, and to conduct special or clandestine operations that were not carried out by other federal agencies or branches of the military. Throughout the war, the OSS provided policy makers and the military with essential intelligence, including enemy troop strength estimates, that was crucial to planning military campaigns.

In the months and years following World War II, policy makers struggled with two questions: Who should conduct the nation's intelligence-gathering activities? And who should supervise their efforts? These were important questions, for the Cold War rivalry between the United States and its chief adversary, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or Soviet Union, made accurate and timely intelligence about Soviet intentions imperative. Initially, President Harry S. Truman favored dividing responsibilities between military and civilian agencies. In October 1945, he abolished the OSS and transferred its operations to the Departments of War and State. At about the same time, Donovan proposed the formation of a strictly civilian organization that would coordinate intelligence gathering. Such an organization would be authorized to conduct subversive operations abroad, but it would have no police or law-enforcement authority at home. Donovan's plan met with resistance from both the military and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which feared that the plan would lessen their influence. In January, 1946, Truman struck a middle course. He established the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), giving it the authority to coordinate intelligence gathered by existing departments and agencies. The CIG was placed under the supervision of a National Intelligence Authority, which in turn was made up of the president and the secretaries of the State, War, and Navy departments. For the first time in its history, the United States had a peacetime intelligence organization.

The original CIG and the National Intelligence Authority lasted less than two years. In 1947, Congress entered the picture by passing the National Security Act. This act created the National Security Council (NSC) and placed under its authority the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Intelligence gathering was now firmly under the control of civilian authorities, principally the president and his NSC staff.

The growth of the CIA. Throughout the early years, the structure of the CIA changed and its functions were assigned and reassigned to various departments. By the early 1960s, its broad structure had become largely what it is in 2003. Under the supervision of the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), one of any president's chief political appointees, are four major departments, or directorates. The Directorate of Administration supervises the business aspects of the agency, including personnel, logistics, training, and the like. The Directorate of Intelligence is the CIA's analysis arm; it interprets raw information and turns it into useful intelligence for the president and the NSC. The Directorate of Science and Technology employs top scientists to develop ever more sophisticated scientific tools to aid in the intelligence-gathering process. Finally, the Directorate of Operations is the traditionally glamorized component of the CIA, for its agents conduct actual intelligence operations in the field.

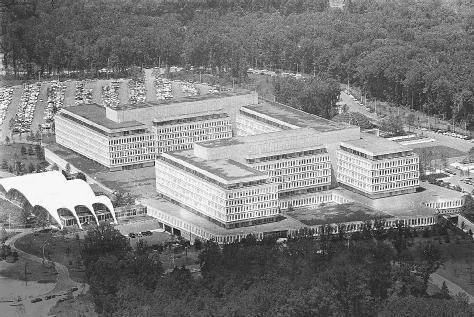

In its early years, the staff of the CIA consisted primarily of former OSS personnel. Until recent years, the CIA was overwhelmingly a male domain, including mostly academics, lawyers, and journalists. At the time, the CIA had a distinctly academic tone, for the agency recruited top students from the nation's most prestigious universities and placed considerable emphasis on the sober analysis of information. In 1950, the CIA employed about 5,000 people who were housed in various locations in and around Washington, D.C. In 1961, the CIA moved into its current headquarters in Langley, Virginia, and continued to grow. Today the exact number of CIA employees is classified (about 20,000; 6,000 of whom serve in clandestine areas of the organization), but one measure of the agency's size is the nation's budget for intelligence-gathering activities, which in 1998 was $26.7 billion.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the CIA enjoyed considerable prestige, for it was primarily through intelligence that the United States resisted the expansion of the Soviet Union and the spread of Communism. The CIA, for example, revealed the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. In the 1960s, however, the CIA began to endure some public opinion scrutiny. In 1961, it backed the disastrous Bay of Pigs operation intended to overthrow Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. Later in the decade, as opposition to the war in Vietnam grew, the CIA was seen in many quarters as emblematic of a misguided foreign policy. Further damaging the agency's reputation were revelations that it took part in unsavory operations in Central and South America, often undermining unfriendly regimes and propping up brutal dictators who were friendly to American interests. In 1975, Senator Frank Church led congressional hearings that resulted in restrictions to the entire intelligence community concerning domestic spying and the implementation of stricter oversight of covert operations abroad. Because of these hearings and revelations, the CIA spent much of the 1980s and 1990s refurbishing its image. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the CIA took on added luster as the nation looked to the agency as the front line in the fight against terrorism. In the wake of the terrorist attacks, the CIA was again granted increased funding and operational authority to pursue counter-terrorism actions.

Directorate of Science and Technology. In its early years, the CIA relied primarily on field operations, but in the early 1960s Director John A. McCone, whose tenure as DCI ran from 1961 to 1965, concluded that the CIA of the future would have to rely more on science and technology. Until that time, the CIA's science and technology efforts had been scattered among various directorates. With the emergence of "overhead" intelligence-gathering technology, including the U-2 spy plane and reconnaissance satellites, McCone gathered all of the agency's scientific and technological capabilities under one roof. The result was the formation of the Directorate of Science and Technology (DS&T) in 1963. Among the DS&T successes are the design and development of high-tech imagery and eavesdropping satellites, including the KH-11 and RHYOLITE. It monitored Soviet missile capabilities from ground stations in China, Norway, and Iran. Its photographic experts played a key role in monitoring such events as the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in the Soviet Union in 1986 and Iraqi troop movements during the 1991 Gulf War. Many of the DS&T's innovations, including heart pacemaker technology, have had implications for medical research.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Ranelagh, John. The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986.

Richelson, Jeffrey T. The Wizards of Langley. Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 2001.

Troy, Thomas F. Donovan and the CIA: A History of the Establishment of the Central Intelligence Agency. Frederick, MD.: University Publications of America, 1981.

ELECTRONIC:

Central Intelligence Agency. "Key Events in CIA's History." < http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/facttell/keyevent.htm > (January 2, 2003).

Federation of American Scientists. "Central Intelligence Agency." September 23, 1996. < http://www.fas.org/irp/cia/ciahist.htm > (January 2, 2003).

SEE ALSO

Bush Administration (1989–1993), United States National

Security Policy

Bush Administration (2001–), United States National Security

Policy

Church Committee

CIA (United States Central Intelligence Agency)

CIA (CSI), Center for the Study of Intelligence

CIA Directorate of Science and Technology (DS&T)

CIA, Foreign Broadcast Information Service

CIA, Legal Restriction

Covert Operations

United States, Counter-Terrorism Policy

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: