Kennedy Administration (1961–1963), United States National Security Policy

█ CARYN E. NEUMANN

President John F. Kennedy entered the White House with confidence that instability in the developing world posed the greatest risk to the national security of the United States. Kennedy planned to resist Soviet expansionism in Latin America, Asia, and Africa by abandoning Eisenhower's policy of massive retaliation in favor of a flexible response, combining economic support with military assistance.

Aggressive and eager to prove himself, Kennedy viewed the Cold War as a struggle of good against evil that required tough action. Through his experiences of World War II, Kennedy held that democracies tended to move too slowly to oppose totalitarianism. He also took note of the narrow margin of victory that had brought him to power and allowed it to shape his security policy. Kennedy tended to defer to military and intelligence experts who favored military action rather than pursue negotiations that would be harder to sell to the American public.

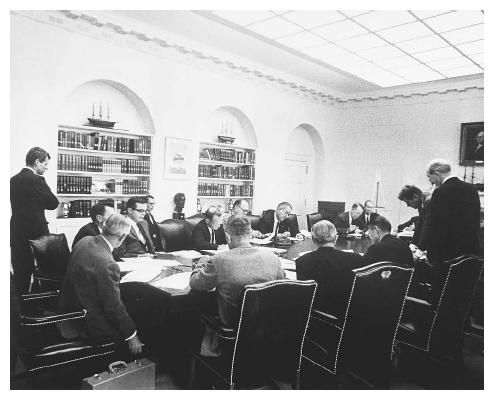

Kennedy's confrontational style did not mesh with the quiet negotiating habits of diplomats in the State Department, and the agency subsequently lost some influence in the White House. The National Security Council (NSC) under adviser McGeorge Bundy increasingly served as an alternate source of policy development and advice at the expense of the State Department under Dean Rusk. This NSC was a far different construct than the one that had served Eisenhower, but it remained focused almost exclusively on foreign policy matters.

While Kennedy would probably have eventually dismantled the elaborate Eisenhower-era NSC in favor of a more open system, the Senate gave him a push. In 1960, the Senate Subcommittee on National Policy Machinery, popularly known as the Jackson Subcommittee for its chairman Senator Henry Jackson, charged that the NSC had been rendered virtually useless by ponderous, bureaucratic machinery. The formality of the NSC system forced the continuation of established policies rather than the generation of new ideas. Heavily influenced by this report, Kennedy deliberately snuffed out the distinction between planning and operation that had governed Eisenhower's NSC, holding that security policy is much more affected by day-to-day events than by any long term planning effort. Kennedy adopted a collegial style of decision-making in which information flows to the president from several competing sources rather than through one bureaucratic process.

The first serious security problem that confronted Kennedy involved intelligence about a purported missile gap between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The missile gap controversy, which dominated the national security debates of the late 1950s and early 1960s, arose from the fear that the Soviets would possess a commanding superiority in intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in just a few years. Both Soviet braggadocio and the American military services encouraged this idea of a missile gap. Two centuries of America's near imperviousness to direct attack appeared at an end. When Kennedy entered office, he discovered the gap was a myth. In order to avoid future self-serving use of intelligence estimates by the military, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara set up the Defense Intelligence Agency to centralize intelligence.

During Kennedy's three years in office, he would work closely with McNamara to supervise the largest and most rapid buildup of military forces in the peacetime history of the U.S. Designed to serve as a deterrent, the buildup provided the nation with an arsenal of both conventional and nuclear armaments. Weaponry included ICBMs and bombers in numbers that dwarfed Soviet forces. This modernization and expansion of the missile system confronted any potential aggressors with the impossibility of a strategic victory and the certainty of total destruction. It also established a direct connection between national security policy and strategic forces procurement.

The Kennedy administration security strategy, called "flexible response" because it expanded the options for fighting the communist threat, rested on three cornerstones. Along with a dramatic increase in the nation's military, Kennedy increased economic and military assistance to the developing world. The Agency for International Development coordinated foreign aid, while the Alliance for Progress acted as a blueprint for Latin America by promoting massive modernization and development. The most celebrated economic aid program offered by the administration was the Peace Corps, established by executive order in 1961. This volunteer group, consisting mostly of young adults, went into developing nations as teachers, agricultural advisers, and technicians. The Peace Corps involved the implicit assumption that technical expertise rather than anti-communist ideology and military dominance would be the best way to win support in the developing world. The last aspect of flexible response aimed to deter aggression by training Latin American paramilitary forces. The Pentagon established the Jungle Warfare School, which taught Latin American police officers how to infiltrate leftist groups.

Kennedy's desire to assist democracy in Latin America led to a serious blunder. As president-elect, Kennedy learned of a secret CIA plan for the invasion of Cuba by anti-communist refugees who had fled the nation when Fidel Castro took power. A few aides expressed doubts about the viability of the plan, but Kennedy was determined to strike against communism in Cuba. The decision to abandon the bureaucratic NSC may have contributed to the resulting debacle. The NSC, which rarely met, did not handle the decision to invade Cuba. The attack, in April 1961, failed within three days. The exposure of U.S. involvement led to widespread international condemnation and a humiliating loss of prestige in Latin America.

In late 1961, an American U-2 spy plane photographed intermediate-range nuclear missile sites in Cuba. Military officials warned Kennedy that the missiles would soon be operational and could strike cities along the East Coast of the United States. If Kennedy declined to respond to the presence of Soviet missiles in the Western Hemisphere, Soviet prestige in the Third World would be bolstered and the communists would gain an important bargaining chip for future negotiations on other issues. After rejecting an air strike to destroy the missiles because the Soviets were likely to respond in a manner that would trigger a general nuclear war, Kennedy imposed a naval blockade of Cuba. The Soviets eventually backed down and removed the missiles, but not before the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. came close to war.

The possibility of nuclear war, brought home by the Cuban missile crisis, led to a softening of Cold War attitudes and a new emphasis on cooperation. The White House and Kremlin agreed to the installation of a "hot line" to establish instantaneous communication between the two superpowers. In 1963, the thaw in relations led to the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which halted atmospheric and underwater nuclear testing.

The Kennedy administration came into office with a determination to continue the aggressive Cold War policies of the past. Although it focused on aid to the developing world, little changed in regard to basic national security policy until 1962. The Cuban missile crisis brought the U.S. to the brink of a possible nuclear war and forced a reexamination of American attitudes toward the Soviet Union and the Cold War.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Ball, Desmond. Politics and Force Levels: The Strategic Missile Program of the Kennedy Administration. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1988.

Boll, Michael M. National Security Planning Roosevelt Through Reagan. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1988.

Crabb, Cecil V., and Kevin V. Mulcahy. American National Security: A Presidential Perspective. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1991.

ELECTRONIC:

White House. "History of the National Security Council, 1947–1997." < http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/history.html > (April 25, 2003).

SEE ALSO

Ballistic Missiles

Bay of Pigs

Berlin Wall

Cold War (1950–1972)

Cuban Missile Crisis

DIA (Defense Intelligence Agency)

Executive Orders and Presidential Directives

National Security Strategy, United States

NSC (National Security Council)

NSC (National Security Council), History

U-2 Spy Plane

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: