Echelon

Echelon is the name for a global surveillance network consisting of ground stations, satellites, and other listening posts, which collectively intercept and analyze worldwide electronic communications. The signals intelligence agencies of five nations—the National Security Agency (NSA) of the United States, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) of the United Kingdom, the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) of Canada, the Defense Signals Directorate (DSD) of Australia, and the Government Communications and Security Bureau (GCSB) of New Zealand—all participate, with NSA as the controlling agency. Beginning in 1998, the governments of the European continent expressed increasing outrage over Echelon. However, their efforts to monitor their own citizens' communications suggest that this anger is not so much because Echelon exists at all, but because it is not under European control.

In 1943, the United States and United Kingdom signed the Brusa (British-U.S.A.) Agreement, which established a framework for the exchange of signals intelligence (SIGINT) between the two nations. Three years later, with the war over, the two signed the UKUSA (U.K.-U.S.A.) agreement of March 5, 1946, which brought together then SIGINT efforts of British, American, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand intelligence. Each UKUSA nation had its own geographic spheres of influence, matched with its listening posts in certain parts of the globe, but the most powerful of the five nations—the United States—remained the unquestioned first among equals. In later years, a

number of other countries, including Denmark, Germany, Norway, and Turkey, signed "third-party" agreements of participation in the UKUSA network.

Over the years, there emerged a network of listening posts and satellites intercepting cables, telephone communications, radio and microwave signals, wireless communications, e-mail, faxes, and other forms of communication traffic. Almost nothing was immune from the system that came to be known as Echelon, whether a telegram sending birthday greetings to a child in Great Britain, or walkie-talkie communications between East German guards on the Berlin Wall. UKUSA participants were forbidden by law from intercepting communications that originate and terminate in their own countries, but the exchange of information between intelligence services effectively rendered these prohibitions moot. Perhaps NSA, for instance, could not monitor communications within the United States, but GCHQ could with impunity, and it was a simple matter to pass this information on to NSA.

The Echelon system seems to have emerged in something like its present form, though at a much less advanced technological stage, during the early 1970s. In the late 1960s, as NSA and GCHQ geared up for the use of satellites on a grand scale, U.S. and British leadership began to recognize the need for interception and processing sites. The first ground station in what came to be known as Echelon was established at Morwenstow, Cornwall, in England, using two large dish antennae to intercept communications across the Atlantic and Indian oceans. Soon NSA built another such station at Yakima, Washington, to intercept communications across the Pacific. Other sites followed, among them Men with Hill in England, Stanley Bay in Hong Kong (dismantled and moved to Australia prior to the Chinese takeover in 1997), and Sugar Grove in West Virginia.

The technology of Echelon. Echelon has its own security compartments: SECRET SPOKE instead of CONFIDENTIAL, UMBRA GAMMA instead of SECRET, and TOP SECRET UMBRA instead of TOP SECRET, a compartment that it trumps for level of secrecy and security classification. Echelon also long ago developed its own wide-area network (WAN), much like the public Internet today, only this network is completely inaccessible to public traffic.

The Echelon wide-area network includes an intelligence news network known as Newsdealer, a TV conference system called Giggle, and other components. E-mail and Web pages have an appearance very much like those of their counterparts in the ordinary world, but again, the similarity ends at the superficial resemblance. Through a system known as Intelink, analysts can browse pages on NSA's server and select specific geographic areas from which to obtain products ranging from video clips and satellite photos to intelligence and status reports, as well as databases.

Dictionaries. As the targets of Echelon eavesdropping have evolved—from cable traffic and land-line telecommunications to cell-phone traffic and e-mails—so have its tools. These include not only satellites, but also computers for filtering traffic to extract relevant data.

Once this was a painstaking process, with analysts surveying reams of sheets by hand, marking them for specific items of intelligence. Today, computers do most of this work, thanks to systems known as dictionaries—a computer programmed to scan data for specific terms and keywords.

Echelon dictionary computers around the world scan the traffic under their purview, not only for their own keywords, but also for those of other agencies. In time, keyword searches may be replaced by the more efficient method of topic analysis, which employs principles similar to those of "fuzzy logic" in an effort to better replicate the selection process that the human itself undergoes, albeit at a much slower rate.

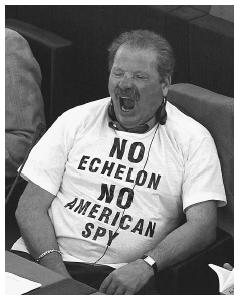

Outrage over Echelon. It has been estimated that for a million inputs (a single phone call being an example of an input), Echelon's dictionaries eliminate all but 6,500 as unimportant. Of these, only 1,000 meet the criteria for forwarding them to analysts, who typically select only 10 for closer study. From these 10, only one warrants the production of an intelligence report. These statistics tend to suggest that, though civil libertarians and others may be outraged over the existence of a system such as Echelon, NSA is really not interested in listening in on most people's phone conversations. It simply sifts through 99.9999 percent of the communication taking place in the world at any given time so as to winnow out the 0.0001 percent that warrants its attention.

Still, concerns about Echelon motivated Margaret "Peg" Newsham, a former computer systems analyst, to release the first reports about the system in 1988. During the early 1990s, New Zealand journalist Nicky Hager painstakingly researched the system to produce his 1996 book Secret Power, and in the late 1990s, respected U.S. intelligence writer Jeff Richelson studied Echelon. The European Union also published a report on Echelon in 2001, in which it called on European citizens to encrypt their emails as a means of protecting them from snooping by the intelligence services of the English-speaking countries. At the same time, the European Union was considering proposals to require Internet service providers and telecommunications companies to record all their customers' communications and archive them for at least a year—a measure that suggests the UKUSA countries do not have the monopoly on snooping in the liberal democratic world, much less in the world as a whole.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Bennett, Richard M. Espionage: An Encyclopedia of Spies and Secrets. London: Virgin Books, 2002.

Best, Richard A. Project Echelon: U.S. Electronic Surveillance Efforts. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2000.

Hager, Nicky. Secret Power. Nelson, New Zealand: Craig Potton, 1996.

Richelson, Jeffrey T. The U.S. Intelligence Community, fourth edition. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999.

PERIODICALS:

Auer, Catherine. "EU Knocks Echelon, Wants Own Super Spy." Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 57, no. 5 (September/October 2001): 11.

Evers, Joris. "U.S. Spy Technology Failed to Signal Attack Planning." InfoWorld 23, no. 38 (September 17, 2001): 28.

Melloan, George. "Civil Liberties Give Way to the Search for Terrorists." Wall Street Journal. (October 23, 2001): A27.

Poole, Patrick. "'Echelon' Spells Trouble for Global Communications." Privacy Journal 25, no. 11 (September 1999): 3–4.

ELECTRONIC:

Campbell, Duncan. Inside Echelon. < http://www.heise.de/tp/english/inhalt/te/6929/1.html > (March 24, 2003).

Easton, Gary. British Broadcasting Corporation News. < http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/h1/world/americas/1577313.stm > (March 24, 2003).

SEE ALSO

COMINT (Communications Intelligence)

Information Warfare

NSA (United States National Security Agency) Satellites, Spy

Security Clearance Investigations

SIGINT (Signals Intelligence)

Special Relationship: Technology Sharing Between the Intelligence

Agencies of the United States and United Kingdom

United Kingdom, Intelligence and Security

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: