Epilepsy - Diagnosis

The first goal of diagnosis is to eliminate other possible causes of the patient's symptoms. Other disorders of the brain, such as small strokes, fainting, and sleep disorders (see sleep disorders entry), can be confused with seizure disorders. A doctor needs to eliminate these possibilities before deciding how to treat the patient.

One goal of diagnosis is to distinguish between symptomatic and idiopathic epilepsy. In symptomatic epilepsy, it may be possible to provide treatment to cure the disorder. For example, a person may have had a severe allergic reaction to a food or drug. The allergic reaction may be responsible for the epileptic attack. This type of case can be treated by avoiding whatever

caused the attack in the first place. In cases of idiopathic epilepsy, where a cause is not found, other types of treatment are necessary.

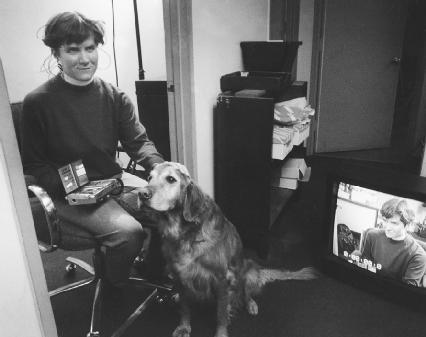

The primary means of diagnosing epilepsy is the electroencephalogram (EEG, pronounced ih-LEK-tro-in-SEH-fuh-lo-gram). The EEG is a device that measures electrical activity in the brain. The results obtained from an EEG test are recorded on graph paper as a pattern of wavy lines. A doctor is able to read the lines on the paper and determine whether or not the brain is functioning normally. Seizure disorders produce characteristic patterns in an EEG test.

Doctors may try to schedule an EEG test during a seizure. They know that flashing lights (like strobe lights) or forcing the patient to breathe very deeply can trigger a seizure in patients with epilepsy. Or the patient may simply be kept in the hospital until an attack occurs. In such cases, the electrical activity of the brain during an attack can be observed and recorded.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: