Diseases of the Digestive System - Stomach and intestines

Indigestion (Dyspepsia)

There are times when the gastrointestinal tract fails to carry out its normal digestive function. The resulting indigestion, or dyspepsia , generates a variety of symptoms, such as heartburn, nausea, pain in the upper abdomen, gases in the stomach ( [xgflatulence[ag ), belching, and a feeling of fullness after eating.

Indigestion can be caused by ulcers of the stomach or duodenum and by excessive or too rapid eating or drinking. It may also be caused by emotional disturbance.

Constipation

Constipation is the difficult or infrequent evacuation of feces. The urge to defecate is normally triggered by the pressure of feces on the rectum and by the intake of food into the stomach. On the toilet, the anal sphincter is relaxed voluntarily, and the fecal material is expelled. The need to defecate should be attended to as soon as possible. Habitual disregard of the desire to empty the bowels reduces intestinal motion and leads to constipation.

Daily or regular bowel movements are not necessary for good health. Normal bowel movements may occur at irregular intervals due to variations in diet, mental stress, and physical activity. For some individuals, normal defecation may take place as infrequently as once every four days.

Simple Constipation

In simple constipation, the patient may have to practice good bowel movement habits, which include a trip to the toilet once daily, preferably after breakfast. Adequate fluid intake and proper diet, including fresh fruits and green vegetables, can help restore regular bowel movement. Laxatives can provide temporary relief, but they inhibit normal bowel function and lead to dependence. When toilet-training young children, parents should encourage but never force them to have regular bowel movements, preferably after breakfast.

Chronic Constipation

Chronic constipation can cause feces to accumulate in the rectum and sigmoid , the terminal section of the colon. The colonic fluid is absorbed and a mass of hard fecal material remains. Such impacted feces often prevent further passage of bowel contents. The individual suffers from abdominal pain with distension and sometimes vomiting. A cleansing enema will relieve the fecal impaction and related symptoms.

In the overall treatment of constipation, the principal cause must be identified and corrected so that normal evacuation can return.

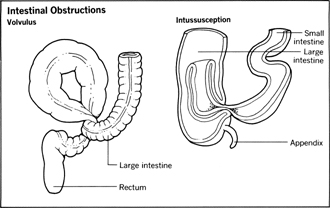

Intestinal Obstructions

Obstruction to the free flow of digestive products may exist either in the stomach or in the small and large intestines. The typical symptoms of intestinal obstruction are constipation, painful abdominal distension, and vomiting. Intestinal obstruction can be caused by the bowel's looping or twisting around itself, forming what is known as a volvulus . Malignant tumors can either block the intestine or press it closed.

In infants, especially boys, a common form of intestinal obstruction occurs when a segment of the intestine folds into the section below it. This condition is known as intussusception , and can significantly reduce the blood supply to the lower bowel segment. The cause may be traced to viral infection, injury to the abdomen, hard food, or a foreign body in the gastrointestinal tract.

The presence of intestinal obstructions is generally determined by consideration of the clinical symptoms, as well as X-ray examinations of the abdomen. Hospitalization is required, since intestinal obstruction has a high fatality rate if proper medical care is not administered. Surgery may be needed to remove the obstruction.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is the frequent and repeated passage of liquid stools. It is usually accompanied by intestinal inflammation, and sometimes by the passing of mucus or blood.

The principal cause of diarrhea is infection in the intestinal tract by microorganisms. Chemical and food poisoning also brings on spasms of diarrhea. Long-standing episodes of diarrhea have been traced to inflammation of the intestinal mucosa, tumors, ulcers, allergies, vitamin deficiency, and in some cases emotional stress. Diarrhea, in conjunction with other symptoms, can also indicate infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the suspected cause of AIDS. See “AIDS” in Ch. 19, Other Diseases of Major Importance .

Patients with diarrhea commonly suffer abdominal cramps, lose weight from chronic attacks, or have vomiting spells. A physician must always be consulted for proper diagnosis and treatment; this is especially important if the attacks continue for more than two or three days. Untreated diarrhea can lead to dehydration and malnutrition; it may be fatal, especially in infants.

Dysentery

Dysentery is caused by microorganisms that thrive in the intestines of infected individuals. Most common are amoebic dysentery , caused by amoebae, and bacillary dysentery , caused by bacteria. The symptoms are diarrhea with blood and pus in the stools, cramps, and fever. The infection is spread from person to person through infected excrement that contaminates food or water. The bacteria and amoebae responsible can also be spread by houseflies which feed on feces as well as on human foods. It is a common tropical disease and can occur wherever human excrement is not disposed of in a sanitary manner.

Dysentery must be treated early to avoid erosion of the intestinal wall. In bacillary dysentery, bed rest and hospitalization are recommended, especially for infants and the aged. Antibiotic drugs may be administered.

In most cases the disease can be spread by healthy human carriers who must be treated to check further spread.

Typhoid

Enteric fever or typhoid is an acute, highly communicable disease caused by the organism Salmonella typhosa . It is sometimes regarded as a tropical disease because epidemic outbreaks are common in tropical areas where careless disposal of feces and urine contaminates food, milk, and water supplies. In any location, tropical or temperate, where unsanitary living predominates, there is always the possibility that the disease can occur. Flies can transmit the disease, as can shellfish that live in typhoid-infested waters.

The typhoid bacilli do their damage to the mucosa of the small intestines. They enter via the oral cavity and stomach and finally reach the lymph nodes and blood vessels in the small bowel.

Symptoms

Following an incubation period of about ten days, general bodily discomfort, fever, headache, nausea, and vomiting are experienced. Other clinical manifestations include abdominal pain with tenderness, greenish diarrhea (or constipation), bloody stools, and mental confusion. It is not unusual for red spots to appear on the body.

If untreated, typhoid victims die within 21 days of the onset of the disease. The cause of death may be perforation of the small bowel, abdominal hemorrhage, toxemia, or other complications such as intestinal inflammation and pneumonia.

Treatment and Prevention

Typhoid victims should be isolated in a hospital with complete bed rest. Diet should be restricted to highly nutritious liquids or preferably intravenous feeding. Destruction of the bacilli is achieved by antibiotic therapy, usually with Chloromycetin.

To prevent the spread of typhoid, disinfect all body refuse, clothing, and utensils of the infected person. Isolation techniques practiced in hospitals prevent local spread. Milk and milk products should always be pasteurized; drinking water should be chlorinated and/or boiled.

Human beings can infect others without themselves becoming ill, usually unaware that they are carriers. Within recent years, a vaccination effective for a year has been developed. People traveling to areas where sanitation practices may be conducive to typhoid should receive this vaccination.

Foreign Bodies in the Alimentary Tract

Anyone who accidentally swallows a foreign body should seek immediate medical aid. Foreign bodies that enter the gastrointestinal tract may cause obstruction anywhere along the tract, including the esophagus. See “Obstruction of the Windpipe” in Ch. 31, Medical Emergencies .

A foreign body in the esophagus may set off a reflex mechanism that causes the trachea to close. The windpipe may have to be opened by means of a tracheostomy (incision in the windpipe) to restore breathing. If the object swallowed is long and sharp-pointed, it may perforate the tract.

Foreign bodies in the esophagus are usually the most troublesome. X-ray studies aid the physician in locating the swallowed object and in determining how best to deal with it.

Small objects may pass through the digestive tract without causing serious problems, but with larger objects, it is sometimes necessary for a surgeon to remove the foreign object.

Ulcers

A peptic ulcer is an eroded area of the mucous membrane of the digestive tract. The most common gastrointestinal ulcers are found in the lower end of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum and are caused by the excessive secretion of gastric acid which erodes the lining membrane in these areas.

Scientists have discovered a bacteria, Helicobacter pylori, that causes 80 percent of gastric ulcers and 95 percent of duodenal ulcers, and that also figures in a small amount of peptic ulcers. The bacteria, which at least half the world's population harbors from an early age, dwells in the mucous lining of either the stomach or duodenum. It is not clear why ulcers appear in only a portion of those testing positive for the bacteria.

The cause of non-Helicobacter pylori ulcers is also uncertain, but any factor that increases gastric acidity may contribute to the condition.

Symptoms

Early ulcer symptoms are gastric hyperacidity and burning abdominal pain that is relieved by eating, vomiting, or the use of antacids. The pain may occur as a dull ache, especially when one's stomach is empty, or it may be sharp and knifelike.

Other manifestations of a peptic ulcer are: nausea associated with heartburn and regurgitation of gastric juice into the esophagus and mouth; excessive gas; poor appetite, with undernourishment and weakness in older victims; and black stools resulting from a bleeding ulcer.

The immediate goal of ulcer therapy is to heal the ulcer; the long-term goal is to prevent its recurrence. An ulcer normally heals through the formation of scar tissue in the ulcer crater. The healing process, under proper medical care, may take several weeks. The disappearance of pain does not necessarily indicate that the ulcer has healed completely, or even partially. The pain and the ulcerative process may recur at regular intervals over periods of weeks or months.

Although treatment can result in complete healing and recovery, some victims of chronic peptic ulcers have a 20-to-30-year history of periodic recurrences. For such patients, ulcer therapy may have to be extended indefinitely to avoid serious complications. If a recurrent ulcer perforates the stomach or intestine, or if it bleeds excessively, it can be quickly fatal. Emergency surgery is always required when perforation and persistent bleeding occur.

Detection and Treatment

Treatment of ulcers depends on the proper diagnosis and appropriate therapy relating to the degree of severity and recurrence of each ulcer. Conventional treatment options include a combination of ulcer diets, which consist of bland foods such as milk, eggs, jellos, custards, creams and cooked cereals; rest and the reduction of stress; and antacids and antispasmodic medication to reduce stomach contraction and acidity and slow digestion. In severe cases, hospitalization and possible surgery may be necessary. Although these treatments still remain common today, the emergence of H pylori as a factor has brought about new treatment options which may eventually replace the vast majority of previous therapies.

Ulcer sufferers should consider a variety of treatment courses, based on cost, severity of the ulcer, and the presence of H. pylori. Patients with mild to moderate ulcer symptoms are urged to undertake a one-to-two month treatment of an H2 blocker, which reduces secretions of gastric acid, and Prilosec, a relatively new acid-suppressing drug. H2 treatment is successful in a third of ulcer cases, with the ulcers reappearing on the average of one year after treatment. Side effects of H2 therapy include mental confusion, fever, and a slowed pulse. Other gastric and limiting drugs have been found to attack the leukocytes or white cells of the blood.

Endoscopy, a costly and sometimes uncomfortable test, has become the preferred procedure for the other two-thirds of patients, especially those whose ulcers do not respond to H2 therapy or other treatments, and where the presence of the H. pylori bacteria is suspected. This ten-to-fifteen minute test, usually outpatient, consists of the physician inserting a lighted tube down the throat into the duodenum and stomach in order to procure a tiny portion of the gastric or duodenal lining for testing. If H. pylori is detected along with an ulcer, the patient undertakes a two-week combination of two antibiotics, Flagyl and either tetracycline or amoxicillin; as well as bismuth sub-salicate (Pepto Bismal). Some physicians may add an H2 blocker such as Tagamet or Pepcid to relieve symptoms and hasten healing. Those with a confirmed history of ulcers can skip endoscopy and be tested for infection, alone, by blood tests that specifically check for the presence of antibodies to H. pylori.

Although this therapy has proven to eradicate ulcers in 92 percent of those afflicted, patients should be aware of a variety of factors regarding treatment options. First, other treatments, including H2 blockers, special diet, and stress reduction, may heal ulcers. Up to 30 percent of antibiotic-treated patients experience side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The risk of drug-resistant bacteria is also a factor if the treatment fails to kill all the bacteria. This indicates a need for prevention of the infection in the first place by improvements in hygiene and sanitation techniques, public awareness, and the development of a vaccine that can protect the public from the bacteria.

Hospitalization may be an option if the ulcer does not respond to H2, antibiotic, or other treatments; if pain persists; or in the instance of an active gastric ulcer. A patient may be hospitalized for three weeks to ensure proper diet and the reduction of emotional stress, from work and personal relationships. During this time, the healing process is monitored by X-rays and other tests.

If there is no improvement after three or four weeks, surgery may be advised. Such surgery is elective, as opposed to the emergency surgery required by large, bleeding or perforated ulcers. After the removal of the acid-producing section of the stomach, some patients may experience weakness and nausea as their digestive system adjusts to the reduced size of the stomach. A proper diet of special foods and fluids, plus sedatives, can alleviate this condition. The chances for complete recovery from surgery are good. For a full description of surgical treatment of peptic ulcers, see “Peptic Ulcers” in Chapter 20, Surgery .

Diverticula

A diverticulum is an abnormal pouch caused by herniation of the mucous membrane of the digestive tract. The pouch has a narrow neck and a bulging round end. Diverticula are found in the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, colon, and other parts of the digestive tract.

The presence of diverticula in any segment of the digestive tract is referred to as diverticulosis . When diverticula become inflamed the condition is known as diverticulitis . The latter is a common form of disease of the sigmoid colon and is found in persons past the age of 45.

In mild cases, there may be no symptoms. On the other hand, a diverticulum may sometimes rupture and produce the same symptoms as an acute attack of appendicitis—vomiting and pain with tenderness in the right lower portion of the abdomen. Other symptoms are intermittent constipation and diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

Diverticulosis is treated by bed rest, restriction of solid food and increase of fluid intake, and administration of antibiotics. Surgery is recommended when diverticulosis causes obstruction of the colon or creates an opening between the colon and the bladder, or when one or more diverticula rupture and perforate the colon. The outlook for recovery following surgery is good.

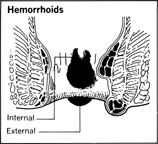

Hemorrhoids (Piles)

Hemorrhoids , or piles , are round, purplish protuberances at the anus. They are the results of rectal veins that become dilated and rupture. Hemorrhoids are very common and are often caused by straining because of constipation, pregnancy, or diarrhea.

Hemorrhoids may appear on the external side of the anus or on the internal side; they may or may not be painful. Rectal bleeding and tenderness are common. It is important to emphasize, however, that not all rectal bleeding results from hemorrhoids. Small hemorrhoids are best left untreated; large painful ones may be surgically reduced or removed. Prolapsed piles—those that have slipped forward—are treated by gentle pressure to return the hemorrhoidal mass into the rectum. The rectal and anal opening must be lubricated to keep the area soft. Other conditions in the large bowel can simulate hemorrhoids and need to be adequately investigated.

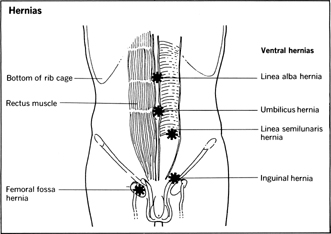

Hernias

Hernias in the digestive tract occur when there is muscular weakness in surrounding body structures. Pressure from the gastrointestinal tract may cause a protrusion or herniation of the gut through the weakened wall. Such hernias exist in the diaphragmatic area ( hiatus hernias , discussed above), in the anterior abdomen ( ventral hernias ), or in the region of the groin ( inguinal hernias ). Apart from hiatus hernias, inguinal hernias are by far the most common.

One of the causes of intestinal obstruction is a strangulated hernia . A loop of herniated bowel becomes tightly constricted, blood supply is cut off, and the loop becomes gangrenous. Immediate surgery is required since life is threatened from further complications.

Except for hiatus hernias, diagnosis is usually made simple by the plainly visible herniated part. In men, an enlarged scrotum may be present in untreated inguinal hernias. The herniating bowel can be reduced, that is, manipulated back into position, and a truss worn to support the reduced hernia and provide temporary relief. In all hernias, however, surgical repair is the usual treatment.

Gastritis

Gastritis is inflammation of the mucosa of the stomach. The patient complains of epigastric pain—in the middle of the upper abdomen—with distension of the stomach, loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting.

Attacks of acute gastritis can be traced to bacterial action, food poisoning, peptic ulcer, the presence of alcohol in the stomach, the ingestion of highly spiced foods, or overeating and drinking. Occasional gastritis, though painful, may disappear spontaneously. Gastritis may also cause serious bleeding. The general treatment for gastritis is similar to the treatment of a gastric ulcer.

Enteritis

Enteritis , sometimes referred to as regional enteritis , is a chronic inflammatory condition of unknown origin that affects the small intestine. It is called regional because the disease most often involves the terminal ileum, even though any segment of the digestive tract can be involved. The diseased bowel becomes involved with multiple ulcer craters and ultimately stiffens because of fibrous healing of the ulcers.

Regional enteritis occurs most often in males from adolescence to middle age. The symptoms may exist for a long period before the disease is recognized. Intermittent bloody diarrhea, general weakness, and lassitude are the early manifestations. Later stages of the disease are marked by fever, increased bouts of diarrhea with resultant weight loss, and sharp lower abdominal pain on the right side. This last symptom sometimes causes the disease to be confused with appendicitis, because in both conditions there is nausea and vomiting. Occasionally in women there may be episodes of painful menstruation.

Treatment involves either surgical removal of the diseased bowel or conservative medical management and drug therapy. In acute attacks of enteritis, bed rest and intravenous fluids are two important aspects of treatment. Medical management in less severe occurrences includes a daily diet rich in proteins and vitamins, excluding harder foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables. Antibiotics are prescribed to combat bacterial invasion.

Colitis

Colitis is an inflammatory condition of the colon, of uncertain origin, and often chronic. It may result from a nervous predisposition which leads to bacterial or viral infection. The inflammation can cause spasms that damage the colon, or can lead to bleeding ulcers that may be fatal.

In milder forms, colitis first appears with diarrhea in which red bloody streaks can be observed. The symptoms may come and go for weeks before the effects become very significant. As the disease process advances, the diarrhea episodes become more frequent; more blood and mucus are present in the feces. These are combined with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Because of the loss of blood, the patient often becomes anemic and thin. If there are ulcer craters in the mucosa, the disease is called ulcerative colitis .

Hospitalization is necessary in order to provide proper treatment that will have a long-term effect. Surgery is sometimes necessary if an acute attack has been complicated by perforation of the intestines or if chronic colitis fails to respond to medical management.

Nonoperative treatment includes control of diarrhea and vomiting by drug therapy. Antibiotics are given to control infection and reduce fever, which always accompanies infection. A high protein and vitamin diet is necessary. But if the diarrhea and vomiting persist, intravenous feeding becomes a must. Blood transfusions may be required for individuals who have had severe rectal bleeding. Because there is no absolute cure, the disease may recur.

Appendicitis

The vermiform appendix is a narrow tubular attachment to the colon. It can become obstructed by the presence of undigested food such as small seeds from fruits or by hard bits of feces. This irritates the appendix and causes inflammation to set in. If it is obstructed, pressure builds within the appendix because of increasing secretions, a situation that can result in rupture of the appendix. A ruptured appendix can be rapidly fatal if peritonitis , inflammation of the peritoneal cavity, sets in.

In most cases the onset of appendicitis is heralded by an acute attack of pain in the center of the abdomen. The pain intensity increases, shifts to the right lower abdomen with nausea, vomiting, and fever as added symptoms. Some individuals, however, suffer from recurrent attacks of dull pain without other signs of gastrointestinal disease, and these may not be significant enough to warrant immediate hospitalization.

Diagnosis of appendicitis is usually dependent on the above symptoms, along with tenderness in the appendix area, increased pulse rate, and decreasing blood pressure. The last two are very significant if the appendix ruptures and peritonitis sets in. Whenever these symptoms are observed, the patient should be rushed to the nearest hospital.

Immediate surgical removal of the diseased appendix by means of a small incision is necessary in all nonperforated acute cases. This type of operation ( appendectomy ) is no longer considered major surgery. If the appendix ruptures and peritonitis is evident, emergency major surgery is necessary to drain the infection and remove the appendix. In the absence of postoperative complications, the patient recovers completely. One of the major problems of appendicitis is early diagnosis to prevent dangerous complications.

Intestinal Parasites

Not all the diseases of man are caused by microscopic organisms. Some are caused by parasitic worms, helminths , which invade the digestive tract, most often via food and water. In recent years government health agencies have largely eliminated the prime sources of worm infection: unwholesome meat or untreated sewage that finds its way into drinking water. Nevertheless, helminths still exist. Drugs used to expel worms are called vermifuges or anthelmintics .

The following are among the major intestinal parasites.

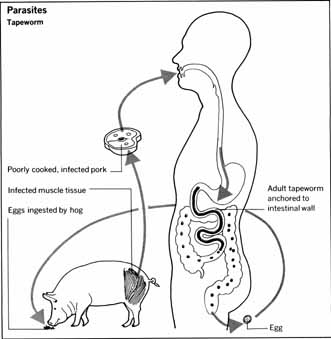

Tapeworms (Cestodes)

These ribbon-shaped flatworms are found primarily in beef, fish, and pork that have not been thoroughly cooked. There are several species ranging from inch-long worms to tapeworms that grow to about 30 feet and live for as long as 16 years.

Tapeworms attach themselves to intestinal mucosa and periodically expel their eggs in excreta. If such feces are carelessly disposed of, the eggs can reach drinking water and be taken in by fish or ingested by grazing cattle. The eggs hatch in the animal's large bowel and find their way into the bloodstream by boring through the intestinal wall. Once in the blood they eventually adhere to muscles and live a dormant life in a capsule.

People who eat raw or partially cooked meat and fish that are infested with tapeworms become infected. The worms enter the bowel, where they feed, grow, and produce eggs. When the egg-filled segments are excreted, the cycle begins anew. Tapeworm infection is usually asymptomatic. It is discovered when egg-laden segments in feces are recognized as such.

Medication must be given on an empty stomach, followed later by a laxative. This will dislodge the worms and enable the body to purge itself of them. A weekly check of stools for segments of the worms may be necessary to confirm that the host is free of the parasites.

Hookworms

There are many species of these tiny, threadlike worms which are usually less than one centimeter long. They are found principally in tropical and subtropical areas of China, North Africa, Europe, Central America, and the West Indies, but they are by no means extinct in the United States.

The eggs are excreted in the feces of infected individuals, and if fecal materials are not well disposed of, the eggs may be found on the ground of unsanitary areas. In warm, moist conditions they hatch into larvae that penetrate the skin, especially the feet of people who walk around barefooted. The larvae can also be swallowed in impure water.

Hookworm-infected individuals, most often children, may experience an inflammatory itch in the area where the larvae entered. The host becomes anemic from blood loss, due to parasitic feeding of the worms, develops a cough, and experiences abdominal pain with diarrhea. Sometimes there is nausea or a distended abdomen. Diagnosis is confirmed by laboratory analysis of feces for the presence of eggs.

Successful treatment requires administration of anthelmintic drugs, preferably before breakfast, to destroy the worms. Weekly laboratory examination of the feces for evidence of hookworm eggs is a necessary precaution in ascertaining that the disease has been eradicated. Untreated hookworm infestation often leads to small bowel obstruction.

Trichinosis

This sometimes fatal disease is caused by a tiny worm, Trichinella spiralis , which is spread to man by eating improperly cooked pork containing the tiny worms in a capsulated form. After they are ingested the worms are set free to attach themselves to the mucosa of the small intestines. Here they mature in a few days and mate; the male dies and the female lays eggs that reach the muscles via the vascular system.

Trichinella organisms cause irritation of the intestinal mucosa. The infected individual suffers from abdominal pains with diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Later stages of the disease are marked by stiffness, pain, and swelling in the muscles, fever with sweating, respiratory distress, insomnia, and swelling of the face and eyelids. Death may result from complications such as pneumonia, heart damage, or respiratory failure. Despite government inspection of meats, all pork should be well-cooked before eating.

Threadworms (Nematodes)

These worms, also called pinworms, infect children more often than adults. Infection occurs by way of the mouth. The worms live in the bowel and sometimes journey through the anus, where they cause intense itching. The eggs are laid at the anal opening, and can be blown about in the air and spread in that manner. The entire family must be medically treated to kill the egg-laying females, and soothing ointment should be applied at the rectal area to relieve the itching. Good personal hygiene, especially hand washing after toilet use, is an essential part of the treatment.

Roundworms (Ascaris)

These intestinal parasites closely resemble earthworms. The eggs enter the digestive tract and hatch in the small bowel. The young parasites then penetrate the walls of the bowel, enter the bloodstream, and find their way to the liver, heart, and lungs.

Untreated roundworm infestation leads to intestinal obstruction or blockage of pancreatic and bile ducts caused by the masses of round-worms, which usually exist in the hundreds. Ingestion of vermifuge drugs is the required treatment.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: