Secret Service, United States

The United States Secret Service (USSS) has two missions that, while sharply distinguished from one another, are united by the principle of protection. On the one hand, in its more visible role, the service provides protection of the president, vice president, and other dignitaries and their families. On the other hand, USSS's larger mission protects securities, including federal currency and other documents. Established in 1865 as an office under the Department of the Treasury, USSS was transferred in 2003 to the newly created Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Early history. At the time Secret Service was founded, approximately one-third of all currency in circulation was counterfeit. Only in 1877 did Congress pass its first law against the production of counterfeit currency, and even then, the law only encompassed counterfeit coins. By then, the mission of USSS had broadened, with an order in 1867 charging it with "detecting persons perpetrating frauds against the government"—a mission that soon put the service on the trail of a range of lawbreakers ranging from bootleggers to members of the Ku Klux Klan.

The personal protection mission of USSS had its beginnings in 1894, when it first provided protection to President Grover Cleveland on an informal and part-time basis. Following the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901, Congress officially requested USSS protection for presidents, and in 1902 the Secret Service assumed full-time protective duties for the Chief Executive. At that time, the White House detail numbered just two agents.

The first half of the twentieth century. In 1908 President Theodore Roosevelt transferred eight USSS agents to the Department of Justice, where they formed a small contingent that would ultimately become the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Congress in 1913 authorized USSS to provide permanent protection to U.S. presidents, and in

1917 it assigned them to protect presidents' immediate families as well. Also in that year, it became a federal crime to make threats against the president. At the request of President Warren G. Harding, a White House police force was created in 1922, and in 1930 Congress placed this force under USSS direction.

On November 1, 1950, Puerto Rican nationalists attempting to assassinate President Harry S Truman shot and killed White House police officer Leslie Coffelt. This led Congress to pass legislation formalizing USSS permanent protection for presidents and their immediate families, as well for the president-elect and the vice president. In 1962 Congress again expanded these provisions to include the vice president-elect.

The modern Secret Service. After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, awareness of the threat to presidents' lives increased dramatically. The mission of USSS also expanded with regard to the persons under its protection. Congress in late 1963 authorized protection for Mrs. Kennedy and her children for two years, and legislation in 1965 provided protection for a president's spouse, as well as minor children until the age of 16. In June 1968, while on the presidential campaign trail, Kennedy's brother, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, was assassinated. This led to new laws providing Secret Service protection for major presidential and vice presidential candidates and nominees.

The White House Police Force became the Executive Protective Service in 1970, and to its duties was added responsibility for protecting diplomatic missions in Washington, D.C. In the next year, visiting heads of state or government, as well as other official guests, were granted USSS protection. By 1975, the Executive Protective Service was detailed to guard foreign diplomatic missions throughout the United States and its territories. On November 15, 1977, the Executive Protective Service became the Secret Service Uniformed Division, and in October 1986 it absorbed the Treasury Police Force.

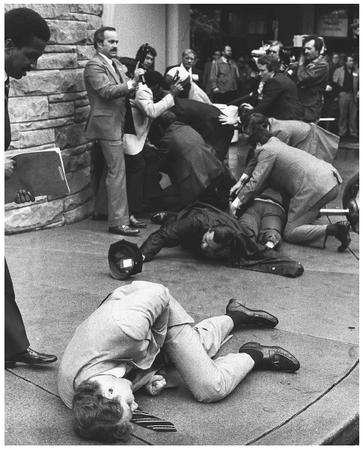

Since the Kennedy assassination, only three persons under Secret Service protection have been the target of direct assassination attempts: Alabama governor and third-party presidential candidate George Wallace in 1972, President Gerald Ford in 1975 (twice), and President Ronald Reagan in 1981. All three survived, a circumstance that— particularly in the last instance, when several agents were wounded—owed much to the work of Secret Service.

From the 1980s onward. At the same time, USSS continued work in its other field, protecting securities. In 1984 Congress made credit-and debit-card fraud a federal violation, and authorized Secret Service to investigate those crimes, as well as fraud involving identification documents. USSS in 1990 received concurrent jurisdiction with Department of Justice law enforcement personnel to conduct civil and criminal investigations relating to federally insured financial institutions. In 1994 new legislation provided for the prosecution of persons counterfeiting U.S. currency abroad, assessing them with the same penalties as if they had committed the crime on American soil.

Also in 1994, Congress reduced the lifetime-protection provisions for presidents. All chief executives elected after January 1, 1997, would receive protection only for the first 10 years after leaving office. Under the provisions of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, Secret Service moved to the new DHS.

Though its headquarters are in Washington, D.C., just three blocks from the White House, Secret Service operates more than 120 field offices in all 50 U.S. states. It also has more than a dozen offices in foreign countries. It employs 2,100 special agents, another 1,200 uniformed agents, and some 1,700 support personnel.

Uniformed and special agents. Requirements for special agents are somewhat higher than for uniformed officers— for example, a bachelor's degree is a condition of eligibility for the former and not the latter—but standards for both are high, and applicants must pass an extensive series of tests and background checks. Those selected by Secret Service undergo a nine-week training course at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Glynco, Georgia, followed by specialized training. Special-agent candidates take an additional 11-week course at the Secret Service Training Academy in Beltsville, Maryland. Uniformed officers receive varying types of training.

Agents serving in the Uniformed Division provide protection at the White House and a number of other key sites in Washington. They often work with support teams that include countersniper, emergency response, and canine units. Special agents usually spend their first six to eight years in a field office, then are assigned to provide personal protection for three to five years. After this assignment, they may choose a number of paths, continuing in a protective detail, serving in the field, or working in some other capacity.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Department of the Treasury. Excerpts from the History of the United States Secret Service, 1865–1875. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Treasury, 1978.

McCarthy, Dennis V. N. with Philip W. Smith. Protecting the President: The Inside Story of a Secret Service Agent. New York: William Morrow, 1985.

Melanson, Philip H. The Politics of Protection: The U.S. Secret Service in the Terrorist Age. New York: Praeger, 1984.

Motto, Carmine J. In Crime's Way: A Generation of U.S. Secret Service Adventures. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2000.

ELECTRONIC:

United States Secret Service. < http://www.ustreas.gov/usss/ > (February 5, 2003).

SEE ALSO

Counterfeit Currency, Technology and the Manufacture

Engraving and Printing, United States Bureau

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: