Manhattan Project

█ BRENDA WILMOTH LERNER

The Manhattan Project was an epic, secret, wartime effort to design and build the world's first nuclear weapon. Commanding the efforts of the world's greatest physicists and mathematicians during World War II, the $20 billion project resulted in the production of the first uranium and plutonium bombs. The American quest for nuclear explosives was driven by the fear that Hitler's Germany would invent them first and thereby gain a decisive military advantage. The monumental project took less than four years, and encompassed construction of vast facilities in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington, that

were used for the purpose of obtaining sufficient quantities of the isotopes uranium-235 and plutonium-239, necessary to produce the fission chain reaction, which released the bombs' destructive energy. After a successful test in Alamogordo, New Mexico, the United States exploded a nuclear bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Three days later another bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki, and spurred the Japanese surrender that ended World War II.

In the 1930s and early 1940s, fundamental discoveries regarding the neutron and atomic physics allowed for the possibility of induced nuclear chain reactions. Danish physicist Neils Bohr's (1885–1962) compound nucleus theory, for example, laid the foundation for the theoretical exploration of fission, the process whereby the central part of an atom, the nucleus, absorbs a neutron, then breaks into two equal fragments. In certain elements, such as plutonium-239, the fragments release other neutrons which quickly break up more atoms, creating a chain reaction that releases large amounts of heat and radiation.

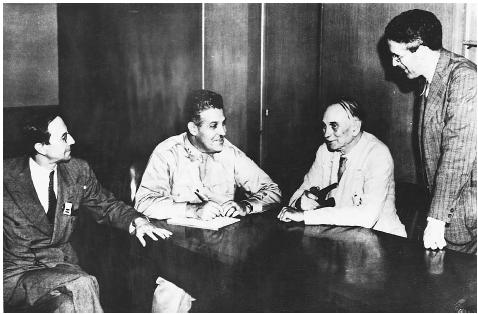

Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard (1898–1964) conceived the idea of the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, and immediately became concerned that, if practical, nuclear energy could be used to make weapons of war. Szilard, who fled Nazi persecution first in his native Hungary, then again in Germany, conveyed his concerns to his friend and contemporary, noted physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955). In 1939, the two scientists drafted a letter (addressed from Einstein) warning United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the plausibility of nuclear weapons, and of German experimentation with uranium and fission. In December, 1941, after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor and the United States' entry into the war, Roosevelt ordered a secret United States project to investigate the potential development of atomic weapons. The Army Corps of Engineers took over and in 1942 consolidated various atomic research projects into the intentionally misnamed Manhattan Engineering District (now commonly known as the Manhattan Project), which was placed under the command of Army Brigadier General Leslie Richard Groves.

Groves recruited American physicist Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967) to be the scientific director for the Manhattan Project. Security concerns required the development of a central laboratory for physics weapon research in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Oppenheimer's leadership attracted many top young scientists, including American physicist Richard Feynman (1918–1988), who joined the Manhattan Project while still a graduate student. Feynman and his mentor Hans Bethe (1906–) calculated the critical mass fissionable material necessary to begin a chain reaction.

Fuel for the nuclear reaction was a primary concern. At the outset, the only materials seemingly satisfactory for sustaining an explosive chain reaction were either U-235 (derived from U-238) or P-239 (an isotope of the yet unsynthesized element plutonium). Additional requirements included an abundant supply of heavy water (e.g., deuterium and tritium). At Oak Ridge, the process of gaseous diffusion was used to extract the U-235 isotope from uranium ore. At Hanford, production of P-239 was eventually made possible by leaving plutonium-238 in a nuclear reactor for an extended period of time.

In 1942, Italian physicist Enrico Fermi (1901–1954) supervised the first controlled sustained chain reaction at the University of Chicago. Underneath the university football stadium, in modified squash courts, Fermi and his team assembled a lattice of 57 layers of uranium metal and uranium oxide embedded in graphite blocks to create the first reactor pile.

The Manhattan Project eventually produced four bombs. Little Boy, the code name for the uranium bomb, utilized explosives to crash pieces of uranium together to begin an explosive chain reaction. Fat Man, the code name for the plutonium bomb, was more difficult to design. It required a neutron-emitting source to initiate a chain reaction within a series of concentric nested spheres. The outermost shell was an explosive lens system surrounding a pusher/neutron absorber shell designed to reduce the effect of Taylor waves, the rapid drop in pressure that occurs behind a detonation front and could interfere with an implosion. The next nested sphere was a uranium tamper/reflector shell containing a plutonium pit and beryllium neutron initiator. The spheres were designed to implode, causing the plutonium to fuse, reach critical mass, then start the reaction

The simple design of the uranium bomb left scientists confident of its success, but the complicated implosion trigger required by the plutonium bomb raised engineering concerns about reliability. On July 16, 1945, a plutonium test bomb code named Gadget was detonated in a remote area near Alamogordo, New Mexico. Observed by scientists wearing only welder's glasses and suntan lotion for protection, the test blast (code named Trinity) was more powerful than originally thought, roughly equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT, and caused total destruction up to one mile from the blast center.

Protecting the secrecy of the Manhattan Project was one of the most complex intelligence and security operations during the war. At the Los Alamos facility, all residents were confined to the project area and surrounding town. Though several leading scientists knew the nature and scope of the entire project, most lab facilities were compartmentalized with various teams working on different project elements. Those who worked in the lab were forbidden to discuss any aspect of the project with friends or relatives. Military security personnel guarded the grounds and monitored communications between research teams. Official communications outside of Los Alamos, especially to the other Manhattan Project sites, were coded and enciphered. Mail was permitted, but heavily censored. Since the actual location of the Los Alamos facility was secret, all residents used the clandestine address "Box 1663, Santa Fe, New Mexico," for correspondence.

Communities were created around other project sites as well. The government created the towns of Oak Ridge and Hanford, relocating thousands of area residents before beginning construction. The towns, thus secured for facility personnel and their families, placed severe restrictions on civilian activities. In some areas, private telephones and radios were prohibited. Residents were encouraged to use simple pseudonyms outside of the lab. Children did not use their full names in school in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Managing several different facilities, spaced nearly two thousand miles apart, raised some significant security challenges. Communication was limited, and incoming and outgoing traffic from facility areas was closely monitored. Security of key documents was a constant concern. The isolated locations of the sites helped to insulate them from enemy espionage. However, the separate locations were also a key security strategy. Breaking the Manhattan Project into various smaller operations prevented jeopardizing the entire project in the event of a nuclear accident. The compartmentalization of such projects remains a common practice.

On August 6, 1945, an American B-29 "Flying Fortress," the Enola Gay, dropped the uranium bomb over Hiroshima. Sixty thousand people were killed instantly, and another 200,000 subsequently died as a result of burn and radiation injuries. Three days later, a plutonium bomb was dropped over Nagasaki. Although it missed its actual target by over a mile, the more powerful plutonium bomb killed or injured more than 65,000 people and destroyed half of the city. Ironically, ground zero, the point under the bomb explosion, turned out to be the Mitsubishi Arms Manufacturing Plant, at one time the major military target in Nagasaki. The fourth bomb remained unused.

Many Manhattan Project scientists eventually became advocates of the peaceful use of nuclear power and advocates for nuclear weapons control.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Fermi, Rachel, and Esther Samra. Picturing the Bomb: Photographs from the Secret World of the Manhattan Project. New York: H. N. Abrams, 1995.

Norris, Richard. Racing For the Bomb: General Leslie R. Groves, the Manhattan Project's Indespensable Man. South Royalton, VT: Steerforth Press, 2002.

Rhodes, Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Touchstone, 1995 (reprint).

ELECTRONIC:

Los Alamos National Laboratory. Manhattan Project History. "The Italian Navigator Has Landed in the New World. Secret Race Won with Chicago's Chain Reaction" < http://www.lanl.gov/worldview/welcome/history.shtml > (February, 24, 2003).

National Atomic Museum, Albuquerque, New Mexico. "The Manhattan Project." < http://www.atomicmuseum.com/tour/manhattanproject.cfm > (February 24, 2003).

SEE ALSO

Heavy Water Technology

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Nuclear Detection Devices

Nuclear Reactors

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), United States

Nuclear Weapons

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL)

Quantum Physics: Applications to Espionage, Intelligence, and Security

Issues

Weapons of Mass Destruction

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: