Document Destruction

█ JUDSON KNIGHT

Modern society that has become so accustomed to the digitization of data may forget just how much information remains available in physical format. Even documents stored on a computer may circulate as hard copy, and these, combined with other paper items such as phone messages, notes, memoranda, and other items provide an opportunity for the theft of useful information. Businesses targeted for economic espionage are particularly vulnerable, as are individuals, either due to their own carelessness or that of companies charged with maintaining sensitive records. For that reason, businesses have increasingly turned to document destruction, a security solution long applied by government agencies. Document destruction can be achieved with shredders, burn boxes, and other forms of technology, often in industrial facilities dedicated to that purpose.

Stories of document destruction by businesses and public officials regularly appear in the media. In 2002, as a scandal erupted around Enron Corporation for falsifying records of earnings, it was revealed that Arthur Andersen LLP, the accounting firm that had helped Enron falsify its books, had shredded literally tons of documents.

Other businesses employ document destruction for much more legitimate reasons, such as protection against economic espionage. But not only businesses need to destroy documents; so do individuals. According to the United States Postal Service, half a million people each year become victims of identity theft, which occurs when a criminal steals financial information from someone, then poses as that person in order to siphon off funds. One of the most significant avenues of vulnerability in this area is the household trash. A person may receive an unsolicited credit card offer and, dismissing it as junk mail, throw it away. Once garbage is placed on the curb for pickup, it is easy for a thief to pick through it, remove the credit card offer, fill it out, send it in, and obtain a "free" card—all courtesy of an innocent consumer who failed to take appropriate precautionary measures.

In the 1990s, these garbage-combing thieves earned the colorful appellation of "dumpster diver". Private detectives, for purposes either laudatory or malign, also obtain a great deal of their information from trash. (So, too, do law-enforcement officers, who take advantage of the fact that material an individual has discarded is open to search without a warrant.) Yet not every aspect of

individual vulnerability to identity theft or invasion of privacy involves those intent on misusing individuals' private records.

Forms of Document Destruction

The best methods of document destruction take place on an industrial scale. The document destruction industry, which primarily serves corporate clients, is estimated to generate $1.5 billion a year in revenue. Whereas only about two dozen companies nationwide were in operation in the early 1980s, by 2002 that number had risen to about 600.

Document shredding, which particularly came to national attention in the wake of the Enron debacle, is only one of many methods of document destruction, though it is the one most frequently used. As a report in the Wall Street Journal noted, "For routine destruction work, many companies use shredding services because even heavyduty office-model shredders tend to choke on anything thicker than about 50 pages—and can be stopped dead in their tracks by a binder clip."

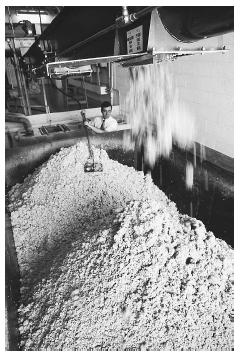

Industrial shredders. By contrast, the shredders at a facility such as that of American Document Security Corporation (ADS) in Brooklyn, New York, are capable of chewing through 20 tons (18.14 tonnes) of documents an hour. Clients of such companies range from law and consulting firms to investment banks, hospitals, and many others.

Though document shredding is probably as old as the concept of written documents, shredding by machine dates back to the 1920s, when an American inventor developed the first shredder from a Bavarian noodle cutter. Today's shredders are far more efficient than those used even in 1979, when the students who took over the U.S. embassy in Teheran, Iran, were able to piece together documents shredded by embassy personnel.

Some shredders are known as disintegrators. Often used for destroying CD ROMs, circuit boards, and other items containing computerized data, these chop up materials into a fine dust that can be sifted through a screen at the bottom of the machine. Another variation on the shredder, inasmuch as it destroys documents by purely physical (rather than chemical or electromagnetic) means, is a hammer-and-mill device, which beats paper quite literally to a pulp.

Burning and other methods. Paper that has been put through industrial shredders and hammer-and-mill devices often is recycled. Waste-to-energy plants burn paper waste at temperatures as high as 2,200° F (1,204 °C).

For burning documents on a smaller scale—especially documents for which security is an extremely high concern—a burn box may be used. Actually, the purpose of the burn box is not to destroy documents per se, but to destroy documents discovered by the wrong people. Inside the box, a sturdy metal container, is a volatile chemical mixture attached to a tamper-sensitive switch. If someone opens the box in an unauthorized manner, the chemicals turn the pages to ash.

A focus on security. An intriguing variety of document destruction can be used for electronic media such as CDROMs, hard drives, floppies, and so on. This is a degausser, which applies electromagnetic energy to rearrange particles of information. Used either in the form of a stationary box or a hand-held wand, a degausser removes information permanently, leaving the storage device free to be used again.

No matter how advanced the technology, however, it is only as reliable as the individual who operates it. For this reason, security concerns are as much a motivator to document-destruction companies as they are to the firms who hire them. ADS, for instance, equips its trucks with alarms, and tracks them on a global positioning system to ensure that documents are not stolen en route. Its employees are bonded, and must undergo background checks prior to employment. Some 30 security cameras are in operation at the Brooklyn facility. Similarly, at the trash-toenergy facility in Utah, a closed circuit television system, along with security guards, provides surveillance during the unloading and burning process.

█ FURTHER READING:

PERIODICALS:

Brown, Ken. "When Enron Auditors Were on a Tear." Wall Street Journal. (March 21, 2002): C1.

Choi, Audrey. "VW Discloses GM Documents Were Destroyed—German Car Maker Denies Involvement, But Rival Still Claims Espionage." Wall Street Journal. (August 9, 1993): A3.

"Document Destruction." Government Executive 30, no. 8 (August 1998): 58.

Eichenwald, Kurt. "Andersen Charged with Obstruction in Enron Inquiry." New York Times. (March 15, 2002): A1.

Kirch, John F. "Document Destruction." Security Management 42, no. 8 (August 1998): 22–23.

Orey, Michael. "Why We Now Need a National Association for Data Destruction." Wall Street Journal. (January 30, 2002): A1.

Rowh, Mark. "Shredders: The Cutting Edge." Office Solutions 19, no. 8 (September/October 2002): 42–44.

ELECTRONIC:

National Association for Information Destruction. < http://www.naidonline.org > (March 30, 2003).

Trujillo, Al. "Avoid Risk with Secure Document Destruction." Electronic and Hardcopy Document Processing Technology. December 2002. < http://www.dptmag.com/editorial2.asp?ID=97 > (March 30, 2003).

SEE ALSO

Computer and Electronic Data, Destruction

Economic Espionage

Privacy: Legal and Ethical Issues

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: