DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration)

█ JUDSON KNIGHT

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is the lead agency of the United States government for the enforcement of federal statutes on narcotics and controlled substances. Created in 1973, it is a division of the Department of Justice with offices throughout the United States, and in 56 countries. DEA has numerous enforcement, education, and interdiction programs, an array as varied as the range of illegal drugs and the variety of groups to which they appeal. Of particular interest within the context of espionage is DEA's intelligence function, much of which is centered at the El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC).

Historical Background

The genealogy of DEA involves entities, not only of the Justice Department, but also of Treasury and even the now-defunct Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). From 1915 to 1927, what traffic in illegal drugs there was in the United States was the purview of Treasury's Bureau of Internal Revenue, which in 1927 turned this responsibility over to the Bureau of Prohibition. In 1930, Treasury established the Bureau of Narcotics, the principal drug-fighting agency of the federal government for more than a generation.

When the government set out to fight illegal drugs during World War I, the use of marijuana and cocaine was a marginal activity, while some synthetic drugs, such as LSD, had yet to be invented. By the mid-1960s, however, the rising culture of psychedelia, closely tied with the antiwar movement and a generalized opposition to "the establishment," had catapulted drug use into the center of the youth culture. Recognizing these changes, HEW in 1966 established the Bureau of Drug Abuse Control within the Food and Drug Administration, and in 1968 this merged with the Bureau of Narcotics to become the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, the first Justice Department incarnation of what was to become DEA.

DEA in the 1970s and 1980s. On July 1, 1973, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs became DEA, which arrived on the scene as drug use was spreading from college

campuses to the mainstream of middle-class life. At no time before or since has drug use been as socially acceptable as it was in the 1970s, and DEA faced an uphill battle both culturally and operationally. The extraordinary growth in marijuana and cocaine use was coupled with a staggering rise in drug traffic from Colombia, Mexico, and other countries, and DEA greatly increased its interdiction efforts at borders, harbors, and airports.

Drug use in the United States reached an all-time high in 1979, and began to steadily decline thereafter. The change is one for which DEA rightly claims considerable credit, but a number of factors contributed. Some were at the level of policy, both public and private, including the "war of drugs" initiated by President Ronald Reagan, the "Just Say No" campaign of First Lady Nancy Reagan, and the efforts of companies who contributed airtime, advertising space, and creative talents to the Partnership for a Drug-Free America. But a societal change was also underway, closely tied with the 1980s emphasis on traditional values, health and fitness, and self-help. By the beginning of the 1990s, Alcoholics Anonymous and other addiction recovery groups were as popular as drugs and alcohol had been a decade earlier.

New drugs and new challenges. Even as drug use became less widespread, the level of commitment to drugs on the part of users deepened. This was accompanied by the rise of ever more dangerous drugs. In the mid-1980s, there was ecstacy, followed by an extraordinarily lethal cocaine derivative called crack. The underpinning of new criminal enterprises, crack spawned an attendant culture in America's inner cities, but the drug knew no ethnic barriers: users of all backgrounds joined the ranks of those addicted to this powerful narcotic.

Just as marijuana and even cocaine had once been mainstreamed among the youth culture as a whole, by the early 1990s one of the most powerful drugs of all, heroin, became a fixture among a much smaller youth segment of "Generation X." Pundits even spoke of "heroin chic," a gaunt look attended by a lackadaisical demeanor and unkempt clothing, which penetrated fashion and culture in general. This was followed a few years later by the surge in popularity of methampethamines and other synthetic stimulants, produced in illegal laboratories across the nation.

September 11, 2001, and narcoterrorism. The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks heightened popular awareness regarding the connection between drugs and terrorism: the Taliban, Al Qaeda's fundamentalist Muslim hosts in Afghanistan, profited from the cultivation of poppies for making opium and heroin. But "narcoterrorism" was nothing new: for years, drug producers in Colombia, Peru, and elsewhere in Latin America had either been in league with, or even controlled by, radical or terrorist groups.

DEA analysts predicted that the connection between terrorism and drugs would only increase, inasmuch as former state sponsors of terrorism had either ceased to exist or had curtailed their activities. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Libya's Muammar Qaddafi had been a prominent sponsor of terrorist groups from Ireland to the Philippines, while the Soviet Union had its hand either directly or indirectly in terrorist activities throughout Western Europe and other regions. Qaddafi became much less involved in terrorism after the 1986 U.S. bombing of Libya, however, and the fall of Soviet Communism cut off millions of dollars in terrorist funding. Terrorists now turned to bank robbery, kidnapping, and drug trafficking to fund their activities.

Mission and Operations

Although it exists to enforce the drug laws of the United States, DEA operates on a worldwide basis. It presents materials to the U.S. civil and criminal justice system, or to any other competent jurisdiction, regarding those individuals and organizations involved in the cultivation, production, smuggling, distribution, or diversion of controlled substances appearing in or destined for illegal traffic in the United States.

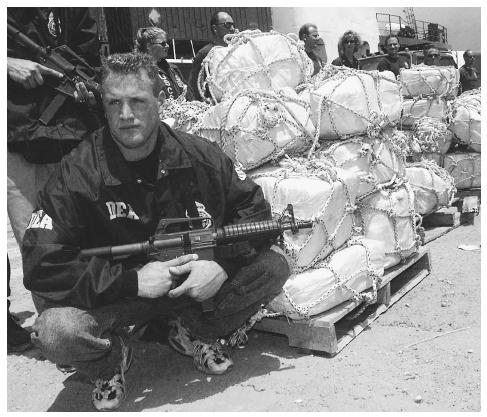

DEA's job is to immobilize those organizations by arresting their members, confiscating their drugs, and seizing their assets. Among its responsibilities are investigation of major narcotics violators operating at the interstate or international levels; seizure of drug-related assets; management of a national narcotics intelligence system; coordination with federal, state, and local law enforcement authorities, as well with counterpart agencies abroad; and training, scientific research, and information exchange in support of prevention and control of drug traffic.

Liaison with other agencies and countries. The liaison between DEA and other agencies exists at all levels, from its relationship with law-enforcement in U.S. cities, towns, and counties to its interaction with the United Nations. DEA also works with INTERPOL and other organizations on matters relating to international narcotics control. Its agents operate throughout the world, with nations who seek to reduce the flow of drugs, and against those few rogue regimes—such as the Taliban in Afghanistan prior to the U.S. victory in late 2001—who profit from the sale of illegal drugs. Exemplary of DEA's worldwide sweep was an August 2002 Washington Post report that it was increasing its presence both along the Mexican border and on the other side of the planet, in Afghanistan, where it was sending 17 additional agents to help control the flow of chemicals used to process heroin.

Particularly significant is DEA's interaction with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). As part of a federal law enforcement reorganization by the Reagan administration, the FBI in January 1982 officially joined forces with DEA so as to greatly increase federal anti-drug efforts. Up to that point, DEA had reported to the associate attorney general—who at that time happened to be future New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani—but thereafter it would answer to the FBI director. At the same time, FBI gained concurrent jurisdiction with DEA where drug offenses were concerned. The result was the increase of the federal anti-drug force to some 10,000 FBI and DEA agents. Two decades later, DEA, a force much smaller than the FBI, was forced to reorganize some of its efforts in light of a post-September, 2001, FBI redirection of 400 agents from drug investigations to counterterrorism.

DEA intelligence. From its beginning, DEA was concerned with the collection, analysis, and dissemination of drug-related intelligence through its Operations Division, which supplied federal, state, local, and foreign officials with information. Originally, the agency had just a few intelligence analysts, but as the need grew, so did the staff, such that by the end of the twentieth century, DEA intelligence personnel—both analysts and special agents—numbered nearly 700.

Along the way, demand for drug-related intelligence became so great that the DEA leadership, recognizing how overtaxed the operations division was, in August, 1992, created the Intelligence Division. The latter consists of four entities: the Office of Intelligence Liaison and Policy, the Office of Investigative Intelligence, the Office of Intelligence Research, and EPIC. The last of these, located in El Paso, Texas, served as a clearinghouse for tactical intelligence (intelligence on which immediate enforcement action can be based) related to worldwide drug movement and smuggling. Eleven federal agencies participate at EPIC in the coordination of intelligence programs related to interdiction.

Other programs and the goals they serve. DEA also creates, manages, and supports domestic and international enforcement programs aimed at reducing the availability and demand for controlled substances. Among its dozens of programs is Demand Reduction, operated by 22 special agents at 21 domestic field divisions to educate youth and communities as a whole, to train law-enforcement personnel, and to encourage drug-free workplaces.

Demand Reduction falls under the heading of the first of three goals DEA established late in the twentieth century, and toward which it continued to work in the early twenty-first. That first goal is to educate and enable America's youth to reject illegal drugs as well as alcohol and tobacco. Among the programs in the service of the second goal—to increase the safety of America's citizens by substantially reducing drug-related crime—are the Mobile Enforcement Teams, which work to dismantle drug organizations.

The third goal, to break foreign and domestic drug sources of supply, places DEA in collaboration with foreign governments and agencies through programs such as the Northern Border Response Force. DEA also works with other federal agencies, including the Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center. DEA intelligence itself serves this third goal.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Levine, Michael. Deep Cover: The Inside Story of How DEA Infighting, Incompetence, and Subterfuge Lost Us the Biggest Battle of the Drug War. New York: Delacorte Press, 1990.

Ojeda, Auriana. Drug Trafficking. San Diego, CA: Green-haven Press, 2002.

Stutman, Robert M., and Richard Esposito. Dead on Delivery: Inside the Drug Wars, Straight from the Street. New York: Warner Books, 1992.

PERIODICALS:

Lichtblau, Eric. "White House Report Stings Drug Agency on Abilities." New York Times. (February 5, 2003): A16.

Reddy, Anitha. "Terrorists Are Now Targets in Money-Laundering Fight." Washington Post. (July 25, 2002): E3.

Schmidt, Susan. "DEA to Bolster Presence along Mexican Border, in Central Asia." Washington Post. (August 10, 2002): A11.

ELECTRONIC:

Drug Enforcement Administration. < http://www.dea.gov > (March 13, 2003).

SEE ALSO

ATF (United States Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms)

Drug Control Policy, United States Office of National

NDIC (Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center)