Africa, Modern U.S. Security Policy and Interventions

█ JUDSON KNIGHT

United States policy in Africa since World War II has generally been non-interventionist, in the sense that U.S. troops have seldom actually engaged in military or quasi-military activities on the African continent. Exceptions, however, do exist, most notable among them being a limited commitment (both of troops and of covert operatives) during the Congo civil war in the early 1960s, the bombing of Libya in 1986, and the humanitarian mission to Somalia in 1993. More often, the United States has provided assistance to African movements, such as anticommunist guerrillas in Angola during the 1970s and 1980s. America has also used diplomatic and economic pressure, both against South African apartheid in the

1980s and criminal activities in Nigeria during the twenty-first century.

Background

After the 1998 embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, the United States conducted bombing raids over both Afghanistan and Sudan, attempting to neutralize Osama bin Laden and his al Qaeda terror network. The fact that the same terrorist group later caused the 2001 bombings in New York City and Washington, D.C., serves to illustrate the fact that events in Africa are not removed from impacting American security and policy. As of July, 2003, the U.S. made a limited troop commitment to secure stability in Liberia and considered a more extensive involvement.

In choosing their policy priorities for Africa, American leaders managed a fine line between appearing interventionist or imperialist on the one hand, and insensitive to Africans' misery on the other. Generally, U.S. policy in Africa has been guided by assessments of the strategic importance of a given nation, its existing alignment or non-alignment with U.S. interests, and the stability of its government.

With the exception of Liberia and Ethiopia, every nation in Africa—more than 50 in all—was at one time a European colony. This is true even in North Africa, whose people are linguistically and culturally distinct from their neighbors to the south. At the beginning of the twentieth century, France held much of west and central Africa; Britain southern and eastern Africa, as well as parts of West Africa; Belgium what is now the Congo, and Portugal a few notable colonies, among them Angola and Mozambique. Germany and Italy, latecomers to African colonialism, controlled some of the sites less rich in natural resources.

In the period between 1945 and 1975, virtually every nation in Africa gained independence, with the Portuguese—first Europeans to colonize in Africa—becoming the last to relinquish colonies. High hopes attended independence, but with few exceptions (a notable one being Botswana), the history of modern Africa has been an unrelieved tale of cruelty, corruption, mismanagement, and rampant disease and poverty. Funds given to help the African people have often ended up in the Swiss bank accounts of dictators, and money intended to build schools and feed children has instead been used to fund civil wars.

The Congo, Rwanda, and Africa's "First World War"

The Congo exemplified this problem. In 1960, Belgium granted its former colony independence, but this proved only the beginning of new troubles. Civil war ensued, and initially the United States, as a participant in a United Nations (UN) peacekeeping force, seemed to back Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. But as Lumumba drifted increasingly into the Soviet orbit, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) considered means of assassinating him, in the words of the local CIA station chief, "to avoid another Cuba." Meanwhile, the United Stated provided assistance to army officer Joseph Désiré Mobutu, whose troops captured and killed Lumumba.

Although conditions in the Congo were difficult under Lumumba, they were at least as bad under Mobutu, who became unquestioned leader of the nation in 1966. He renamed the country Zaire and himself Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga, which means "the all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, will go from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake." For the next three decades, Mobutu, supported by the United States and the World Bank, looted his country, building vast palaces for himself and fattening the pockets of his cronies while the majority of his people lived without electricity, running water, or basic medical care.

Mobutu was overthrown in 1997 by Laurent Kabila, who proved just as corrupt, and who was killed by his own bodyguards in 2001. By then, the Congo had become embroiled in events described collectively as "Africa's First World War." The opening salvo of that larger conflict—a series of conflicts involving Rwanda, the Congo (which returned to its original name in 1997), and other nations—was the infamous Rwandan genocide in 1994.

The conflict involved age-old disputes between the Hutu and Tutsi peoples, who together constitute most of the population in Rwanda, Burundi, and neighboring states. After Rwanda's Hutu dictator, Major General Juvenal Habyarimana, died in a plane crash on April 6, 1994, his supporters blamed the Tutsi-controlled Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), and launched a campaign of genocide that resulted in more than 800,000 deaths over a period of a few weeks. By July, the RPF had driven the remnants of the Habyarimana government, along with some 1 million refugees, into neighboring Zaire. This influx served to so destabilize the Mobutu regime that it helped provide the opportunity for Kabila's takeover.

Somalia, Ethiopia, and Angola: Marxism, Anarchy, and Intervention

The United States was criticized, both at home and abroad, for not intervening in Rwanda, an extremely poor and landlocked nation with almost no strategic importance to Washington. It is possible that had America intervened, it would have been condemned for interfering in other nations' internal affairs. Such was the case in Somalia just a few months earlier, when U.S. attempts to provide humanitarian assistance so inflamed resentment that even after the terrorist attacks of September, 2001, Muslim critics of U.S. policy would cite Somalia as an example of American imperialism.

Located on the horn of Africa, Somalia also achieved its independence in 1960, and also succumbed to dictatorship, in this case under Major General Mohamed Siad Barre. After overthrowing the government in 1969, Siad Barre launched the country on a disastrous experiment in Soviet-style socialism, complete with posters in the capital city of Mogadishu that featured his face alongside those of Karl Marx and V. I. Lenin. In a country where the principal form of organization is by clan, modern political forms of any kind were foreign, and it would have been difficult to find a more inadequate prescription for Somalia's challenges than Siad Barre's Marxist Leninism.

Ironically, the takeover of neighboring Ethiopia by Communists in 1974 proved Siad Barre's undoing. In the chaos that befell Ethiopia after the downfall of longtime emperor Haile Selassie, Somalia went to war with its neighbor over the Ogaden Desert, and by September, 1977, had all but won. At that point, however, the Soviets switched their allegiance to Ethiopia's Marxist government.

The Soviets' change of allegiance created a strange alliance between Siad Barre and the United States. The proxy war in the Horn of Africa nearly became an entanglement involving U.S. troops, as Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Advisor under President James E. Carter, briefly considered deploying the U.S. carrier Kitty Hawk to the region in March 1978. The United States and Somalia concluded military agreements in 1980 that allowed U.S. access to naval ports at Mogadishu and other cities.

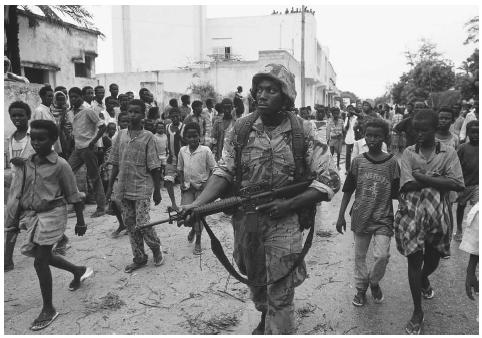

The military alliance with the United States did not result in any meaningful changes in Siad Barre's style of rule, and over the next decade, his influence slowly declined until he was ousted in 1991. By then, with the Cold War all but finished, the United States—which had strategic naval bases farther south in Kenya—had no particular interest in preventing Somalia from sliding toward anarchy. Then, in 1992, during the last weeks of his administration, President George H. W. Bush committed 25,000 U.S. troops to a UN force involved in distributing famine relief supplies.

Bush was influenced by the fact that the UN had performed well during the crises surrounding the Persian Gulf War of 1990–91, but the experience in Somalia was not to be as successful. By 1993, U.S. forces had become caught in the middle of conflicts between local warlords, and on October 3, 18 U.S. Rangers were killed in a firefight on the streets of Mogadishu. Prior to this debacle, Secretary of Defense Les Aspin had outlined an agenda of "nation-building" in a nation that had no true government, and in the aftermath of the Mogadishu disaster, Aspin resigned.

Ethiopia and Somalia were just a few of the nations that attempted to apply the Marxist formula to their problems during the 1970s. Numerous other nations aligned with Moscow, but few did so as openly as the former Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique. The United States provided help to the rebels fighting in both countries, though aid to Angola was much greater. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan, under pressure from both the Department of Defense and the CIA, transferred some $15 million in antiaircraft and antitank missiles to the rebel movement.

The United States commitment to Angola was in part a response to the fact the Soviets and Cubans had become heavily involved on the side of the government, but it was also a product of the magnetism exerted by the rebels' charismatic leader, Jonas Savimbi. In 1966, Savimbi had formed the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, known by the initials of its name in Portuguese, UNITA. First he fought against the Portuguese, then against the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) when it took control of the government after the Portuguese left. Because the MPLA was aligned with Moscow, Savimbi gained support from a wide array of nations opposed to the Soviet Union: the United States, China, and South Africa. Savimbi managed to convince American conservatives that he was an anti-communist, just as he presented himself to the Chinese as a Maoist. To the regime that maintained the system of apartheid in South Africa, Savimbi's victory would help keep blacks from getting the idea that they should gain a share of whites' wealth.

In reality, the war was not about ideology, but about control of the nation's diamond resources and other natural wealth. The Communist regime of José Eduardo dos Santos was corrupt and cruel, but Savimbi matched its record. In 1989, even Mobutu tried to step in and pressure him to accept a ceasefire. In 1992, with the Cold War over, Savimbi lost U.S. funding. He spent the remainder of his life fighting the government and opposition in his party, looting the populace, and resisting efforts toward peace. Six weeks after his death in February, 2002, the two sides signed a ceasefire agreement.

Liberia and South Africa: Oppression and Economics

In deciding to intervene, whether by military, economic, or diplomatic means, prudent leaders tend to favor a conservation of resources. An example was America's response to chaos in Liberia in 1990. The West African nation, founded by freed American slaves in 1847, has proven no more stable or successful than any of its neighbors that had been colonies. Nor has the American influence yet fostered a greater degree of respect for human rights: ironically, the freed slaves, known as Americo-Liberians, virtually enslaved the native Liberians, who lived under conditions of forced labor and extreme poverty.

Finally, in 1980, Sgt. Samuel K. Doe led a revolt against President William Tolbert, ending 133 years of oppression. Doe, however, proved a tyrant, and he benefited from some $500 million in U.S. aid even as the quality of life for the Liberian populace continued to decline. When rebels overthrew Doe in 1990, the United States quietly evacuated its diplomatic personnel and other citizens from the troubled nation.

In part because the nation-state is a western construct imposed on Africa, life in post-colonial times has often been characterized by the oppression of one ethnic group by another: first Hutu by Tutsi, then the reverse, first native Liberians by Americo-Liberians, then the reverse, and so on. As most of these situations involved native African ethnic groups, they have attracted little attention in the outside world. By contrast, the regime of apartheid that prevailed in South Africa for more than four decades after 1948, involving as it did oppression of a black majority by a white minority, invoked sharp criticism throughout the western world.

Although many Americans had long condemned apartheid, the issue did not become a part of American popular culture until 1985, as entertainers and college students took up the cause. Activists pressured the Reagan administration to deal aggressively with South Africa, and to isolate the nation economically. In fact the United States did impose a number of economic restrictions on South Africa, but not to a degree demanded by activists. The solutions that worked with recalcitrant U.S. states during desegregation in the 1960s would not necessarily be as successful with an independent nation in the 1980s. Reagan reasoned that while apartheid did not comport with U.S. values, South Africa was of far greater value to the United States than many of its most outspoken critics—among them Zimbabwe, home to the notorious dictatorship of Robert Mugabe.

Reagan's administration used a combination of limited economic and diplomatic pressure, while allowing South Africans—who at least had a framework of European-style representational government—to work out their own differences. In the end, opposition leader Nelson Mandela was released from prison, apartheid fell, and Mandela became the president of a new South Africa.

Other Interventions and Non-Interventions

In terms of economic intervention, Sierra Leone and Chad may offer positive examples of what the world community can do to affect policy in Africa. In 2000, the UN imposed a ban on the purchase of diamonds from Sierra Leone, sales of which had been used in large part to fund that nation's civil war. Two years later, the 11-year war ended in a ceasefire.

Also in 2000, construction began on a pipeline through Chad, an extremely poor country in which oil had been discovered. Rather than permit a repeat of past mistakes, a consortium of companies (including America's Exxon and Mobil), along with the World Bank, devised a strategy to prevent the nation's rulers from misusing funds. Agreements included stipulations that 80% of all oil revenues would be spent on improving health, education, and welfare for the populace. Another 10% would go into escrow accounts for future generations, 5% would be directed toward the local populations in the area of the oil fields, and only 5% would be placed in the hands of the government to do with as it pleased.

Nigeria: counterfeiting and advance-fee scams. Another economic and legal battleground—one where problems remain is Nigeria. One of the leading nations in Africa in terms of size and potential wealth, with its oil riches, Nigeria is only slightly more stable than its neighbors, and criminal activity is rampant. The country is particularly notorious for its counterfeiting operations and its business scams.

Nigerian counterfeiting involves not banknotes, but consumer and industrial goods, including garments and textiles, electronics, spare parts, pharmaceuticals, personal products, and even soft drinks. The reason, in part, is that intellectual property owners, frustrated with the national bureaucracy, have done little to put a stop to counterfeiting efforts there. Additionally, owners of rights to these products are often unaware of counterfeiting activities in Nigeria. The Nigerian government has injunctions against these crimes, but has been largely ineffective in pursuing them.

In 1999, years of military rule in Nigeria ended, and U.S. officials took advantage of this opportunity to strengthen law enforcement efforts there. In July, 2002, the two countries signed an agreement for increased lawenforcement cooperation. Part of the agreement was a grant of $3.5 million from the United States, intended to help Nigeria modernize its police force and provide additional resources to the country's special fraud unit, which targets 419 known scams.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Campbell, Kurt M., and Michele A. Fluornoy. To Prevail: An American Strategy for the Campaign against Terrorism. Washington, D.C.: CSIS Press, 2001.

Haass, Richard, and Meghan L. O'Sullivan. Honey and Vinegar: Incentives, Sanctions, and Foreign Policy. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2000.

Kissinger, Henry. Years of Renewal. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

Roberts, Brad. U.S. Foreign Policy after the Cold War. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.

ELECTRONIC:

African Issues. U.S. Department of States. < http://usinfo.state.gov/regional/af/ > (April 29, 2003).

Congo Crisis. Maxwell Air Force Base. < http://www.au.af.mil/au/aul/bibs/congo/congo.htm > (April 29, 2003).

USAID in Africa. U.S. Agency for International Development. < http://www.usaid.gov/regions/afr/ > (April 29,2003).

SEE ALSO

Americas, Modern U.S. Security Policy and Interventions

Egypt, Intelligence and Security

IMF (International Monetary Fund)

International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL), United

States Bureau

Kenya, Bombing of United States Embassy

Libya, Intelligence and Security

Libya, U.S. Attack (1986)

Middle East, Modern U.S. Security Policy and Interventions

Morocco, Intelligence and Security

South Africa, Intelligence and Security

Sudan, Intelligence and Security

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: