10.2. Internet/Intranet applications

The Linux system is a great platform for offering networking services. In this section, we will try to give an overview of most common network servers and applications.

| Connecting to the Internet |

|---|---|

Internet connections can be arranged in many different ways; we can not decribe them all in this document, all the more because the connection type is often country or region specific. Check your system documentation and contact your local Internet provider, a local fellow Linux user or your local Linux User Group, see GLUE (Groups of Linux Users Everywhere). |

10.2.1. Server types

10.2.1.1. Standalone server

Offering a service to users can be approached in two ways. A daemon or service can run in standalone mode, or it can be dependent on another service to be activated.

Network services that are heavily and/or continuously used, usually run in the standalone mode: they are independent program daemons that are always running. They are most likely started up at system boot time, and they wait for requests on the specific connection points or ports for which they are set up to listen. When a request comes, it is processed, and the listening continues until the next request. A web server is a typical example: you want it to be available 24 hours a day, and if it is too busy it should create more listening instances to serve simultaneous users. Other examples are the large software archives such as Sourceforge or your Tucows mirror, which must handle thousands of FTP requests per day.

An example of a standalone network service on your home computer might be the named, a caching name server. Standalone services have there own processes running, you can check any time using ps:

bob:~> ps auxw | grep named named 908 0.0 1.0 14876 5108 ? S Mar14 0:07 named -u named |

Most services on your home PC, such as the FTP service, don't have a running daemon, yet you can use them:

bob:~> ps auxw | grep ftp bob 738 690 0 16:17 pts/6 00:00:00 grep ftp bob:~> ncftp localhost NcFTP 3.1.3 (Mar 27, 2002) by Mike Gleason (ncftp@ncftp.com). Connecting to localhost(127.0.0.1)... octarine.hq.soti.org FTP server (Version wu-2.6.2-8) ready. Logging in... Guest login ok, access restrictions apply. Logged in to localhost. ncftp / > |

Let's see in the next section how this is arranged.

10.2.1.2. (x)inetd

On your home PC, things are usually a bit calmer. You may have a small network, for instance, and you may have to transfer files from one PC to another from time to time, using FTP or Samba (for connectivity with MS Windows machines). In those cases, starting all the services which you only need occasionally and having them run all the time would be a waste of resources. So in smaller setups, you will find the necessary daemons dependent on a central program, that listen on all the ports of the services for which it is responsible.

This super-server, the Internet services daemon, is started up at system initialization time. There are two common implementations: inetd and xinetd (the extended Internet services daemon). One or the other is usually running on every Linux system:

bob:~> ps -ef | grep inet root 926 1 0 Mar14 ? 00:00:00 xinetd-ipv6 -stayalive -reuse \ -pidfile /var/run/xinetd.pid |

The services for which the Internet daemon is responsible, are listed in its configuration file, /etc/inetd.conf, for inetd, and in the directory /etc/xinetd.d for xinetd. Commonly managed services include file share and print services, SSH, FTP, telnet, the Samba configuration daemon, talk and time servcies.

As soon as a connection request is received, the central server will start an instance of the required server. Thus, in the example below, when user bob starts an FTP session to the local host, an FTP daemon is running as long as the session is active:

bob:~> ps auxw | grep ftp bob 793 0.1 0.2 3960 1076 pts/6 S 16:44 0:00 ncftp localhost ftp 794 0.7 0.5 5588 2608 ? SN 16:44 0:00 ftpd: localhost.localdomain: anonymous/bob@his.server.com: IDLE |

Of course, the same happens when you open connections to remote hosts: either a daemon answers directly, or a remote (x)inetd starts the service you need and stops it when you quit.

10.2.2. Mail

10.2.2.1. Servers

Sendmail is the standard mail server program or Mail Transport Agent for UNIX platforms. It is robust, scalable, and when properly configured with appropriate hardware, handles thousands of users without blinking. More information about how to configure Sendmail is included with the sendmail and sendmail-cf packages, you may want to read the README and README.cf files in /usr/share/doc/sendmail. The man sendmail and man aliases are also useful.

Qmail is another mail server, gaining popularity because it claims to be more secure than Sendmail. While Sendmail is a monolithic program, Qmail consists of smaller interacting program parts that can be better secured.

These servers handle mailing lists, filtering, virus scanning and much more. Free and commercial scanners are available for use with Linux. Examples of mailing list software are Mailman, Listserv, Majordomo and EZmlm. See the web page of your favorite virus scanner for information on Linux client and server support.

10.2.2.2. Remote mail servers

The most popular protocols to access mail remotely are POP3 and IMAP4. IMAP and POP both allow offline operation, remote access to new mail and they both rely on an SMTP server to send mail.

While POP is a simple protocol, easy to implement and supported by almost any mail client, IMAP is to be preferred because:

It can manipulate persistent message status flags.

It can store as well as fetch mail messages.

It can access and manage multiple mailboxes.

It supports concurrent updates and shared mailboxes.

It is also suitable for accessing Usenet messages and other documents.

IMAP works both on-line and off-line.

it is optimized for on-line performance, especially over low-speed links.

10.2.2.3. Mail user-agents

There are plenty of both text and graphical E-mail clients, we'll just name a few of the common ones. Pick your favorite.

The UNIX mail command has been around for years, even before networking existed. It is a simple interface to send messages and small files to other users, who can then save the message, redirect it, reply to it and such.

While it is not commonly used as a client anymore, the mail program is still useful, for example to mail the output of a command to somebody:

mail <future.employer@whereIwant2work.com> < cv.txt

The elm mail reader is a much needed improvement to mail, and so is pine (Pine Is Not ELM). The mutt mail reader is even more recent and offers features like threading.

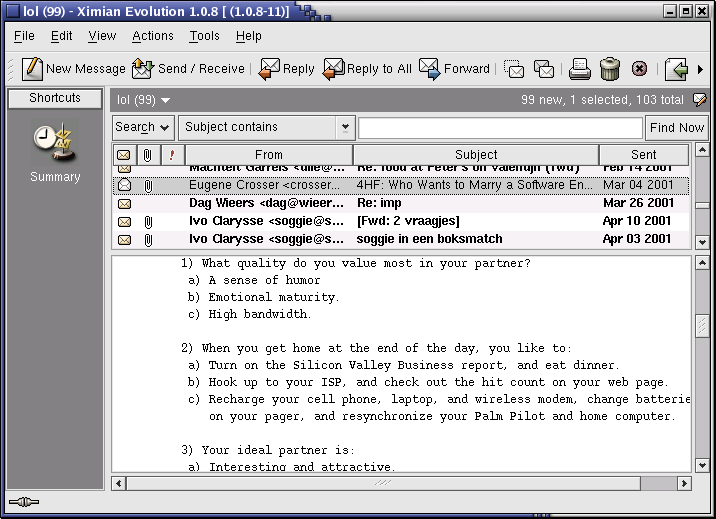

For those users who prefer a graphical interface to their mail (and a tennis elbow or a mouse arm), there are hundreds of options. The most popular for new users are Mozilla Mail and Ximian's MS Exchange clone, Evolution, of which you can see a screenshot below:

There are also tens of webmail applications available.

An overview is available via the Linux Mail User HOWTO.

Most Linux distributions include fetchmail, a mail-retrieval and forwarding utility. It fetches mail from remote mail servers (POP, IMAP and some others) and forwards it to your local delivery system. You can then handle the retrieved mail using normal mail clients. It can be run in daemon mode to repeatedly poll one or more systems at a specified interval. Information and usage examples can be found in the Info pages; the directory /usr/share/doc/fetchmail-<version> contains a full list of features and a FAQ for beginners.

The procmail filter can be used for filtering incoming mail, to create mailing lists, to pre-process mail, to selectively forward mail and more. The accompanying formail program, among others, enables generation of auto-replies and splitting up mailboxes. Procmail has been around for years on UNIX and Linux machines and is a very robust system, designed to work even in the worst circumstances. More information may be found in the /usr/share/doc/procmail-<version> directory and in the man pages.

10.2.3. Web

10.2.3.1. The Apache Web Server

Apache is by far the most popular web server, used on more than half of all Internet web servers. Most Linux distributions include Apache. Apache's advantages include its modular design, SSL support, stability and speed. Given the appropriate hardware and configuration it can support the highest loads.

On Linux systems, the server configuration is usually done in the /etc/httpd directory. The most important configuration file is httpd.conf; it is rather self-explanatory. Should you need help, you can find it in the httpd man page or on the Apache website.

10.2.3.2. Web browsers

A number of web browsers, both free and commercial, exist for the Linux platform. Netscape Navigator has long been the only decent option, but with Mozilla a competitive alternative is available.

Amaya is the W3C browser. Opera is a commercial browser, compact and fast. Many desktop managers offer web browsing features in their file manager, like nautilus.

Among the popular text based browsers are lynx and links. You may need to define proxy servers in your shell, by setting the appropriate variables.

Text browsers are fast and handy when no graphical environment is available, such as when used in scripts. Below is an excerpt from a shell script that acts as a network worm probing available services:

# Is a webserver running on port 80 ? Which version ? tcpcheck 80 if [ -z "$RESULT" ] ; then HTTP="$(lynx -dump -head http://$SERVERIP/|grep '^Server'|\ cut -d" " -f2-)" else HTTP=$(echo "no") fi |

For www.eunet.be, for instance, the result of this lynx probe would be:

eve:~>lynx -dump -head http://www.eunet.be |grep '^Server' |\ cut -d" " -f2 Apache/1.3.14 |

10.2.4. File Transfer Protocol

10.2.4.1. FTP servers

On a Linux system, an FTP server is typically run from xinetd, using the WU-ftpd server, although the FTP server may be configured as a stand-alone server on systems with heavy FTP traffic. See the exercises.

Other FTP servers include among others Ncftpd and Proftpd.

Most Linux distributions contain the anonftp package, which sets up an anonymous FTP server tree and accompanying configuration files.

10.2.4.2. FTP clients

Most Linux distributions include ncftp, an improved version of the common UNIX ftp command, which you may also know from the Windows command line. The ncftp program offers extra features such as a nicer and more comprehensible user interface, file name completion, append and resume functions, bookmarking, session management and more:

thomas:~>ncftp blob NcFTP 3.0.3 (April 15, 2001) by Mike Gleason (ncftp@ncftp.com). Connecting to blubber... blubber.soti.org FTP server (Version wu-2.6.1-20) ready. Logging in... Guest login ok, access restrictions apply. Logged in to blob. ncftp / > help Commands may be abbreviated. 'help showall' shows hidden and unsupported commands. 'help <command>' gives a brief description of <command>. ascii cat help lpage open quote site bgget cd jobs lpwd page rename type bgput chmod lcd lrename pdir rhelp umask bgstart close lchmod lrm pls rm version binary debug lls lrmdir put rmdir bookmark dir lmkdir ls pwd set bookmarks get lookup mkdir quit show ncftp / > |

Excellent help with lot of examples can be found in the man pages. And again, a number of GUI applications are available.

| FTP is insecure! |

|---|---|

Don't use the File Transfer Protocol for non-anonymous login unless you know what you are doing. Your user name and password might be captured by malevolent fellow network users! Use secure FTP instead; the sftp program comes with the Secure SHell suite, see Section 10.3.4. |

10.2.5. Chatting and conferencing

Various clients and systems are available in each distribution. A short and incomplete list of the most popular programs:

gaim: multi-protocol instant messaging client for Linux, Windows and Mac, compatible with MSN Messenger, ICQ, IRC and much more; see the Info pages or the Gaim site for more.

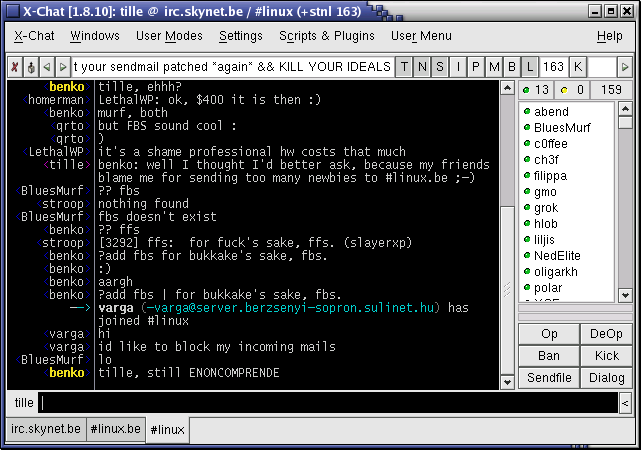

xchat: IRC client for the X window system:

The home page is at SourceForge.

JMSN: Java MSN Messenger clone with many features that the original does not have.

Konversation, KVIrc and many other K-tools from the KDE suite.

gnomemeeting: videoconferencing program for UNIX.

10.2.6. News services

Running a Usenet server involves a lot of expertise and fine-tuning, so refer to the INN homepage for more information.

There are a couple of interesting newsgroups in the comp.* hierarchy, which can be accessed using a variety of text and graphical clients. A lot of mail clients support newsgroup browsing as well, check your program or see your local Open Source software mirror for text clients such as tin, slrnn and mutt, or download Mozilla or one of a number of other graphical clients.

Deja.com keeps a searchable archive of all newsgroups, powered by Google. This is a very powerful instrument for getting help: chances are very high that somebody has encountered your problem, found a solution and posted it in one of the newsgroups.

10.2.7. The Domain Name System

All these applications need DNS services to match IP addresses to host names and vice versa. A DNS server does not know all the IP addresses in the world, but networks with other DNS servers which it can query to find an unknown address. Most UNIX systems can run named, which is part of the bind (Berkeley Internet Name Domain) package distributed by the Internet Software Consortium. It can run as a stand-alone caching nameserver, which is often done on Linux systems in order to speed up network access.

Your main client configuration file is /etc/resolv.conf, which determines the order in which Domain Name Servers are contacted:

search somewhere.org nameserver 192.168.42.1 nameserver 193.74.208.137 |

More information can be found in the Info pages on named, in the /usr/share/doc/bind-<version> files and on the Bind project homepage. The DNS HOWTO covers the use of BIND as a DNS server.

10.2.8. DHCP

DHCP is the Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol, which is gradually replacing good old bootp in larger environments. It is used to control vital networking parameters such as IP addresses and name servers of hosts. DHCP is backward compatible with bootp. For configuring the server, you will need to read the HOWTO.

DHCP client machines will usually be configured using a GUI that configures the dhcpcd, the DHCP client daemon. Check your system documentation if you need to configure your machine as a DHCP client.

10.2.9. Authentication services

10.2.9.1. Traditional

Traditionally, users are authenticated locally, using the information stored in /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow on each system. But even when using a network service for authenticating, the local files will always be present to configure system accounts for administrative use, such as the root account, the daemon accounts and often accounts for additional programs and purposes.

These files are often the first candidates for being examined by hackers, so make sure the permissions and ownerships are strictly set as should be:

bob:~> ls -l /etc/passwd /etc/shadow -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1803 Mar 10 13:08 /etc/passwd -r-------- 1 root root 1116 Mar 10 13:08 /etc/shadow |

10.2.9.2. PAM

Linux can use PAM, the Pluggable Authentication Module, a flexible method of UNIX authentication. Advantages of PAM:

A common authentication scheme that can be used with a wide variety of applications.

PAM can be implemented with various applications without having to recompile the applications to specifically support PAM.

Great flexibility and control over authentication for the administrator and application developer.

Application developers do not need to develop their program to use a particular authentication scheme. Instead, they can focus purely on the details of their program.

The directory /etc/pam.d contains the PAM configuration files (used to be /etc/pam.conf). Each application or service has its own file. Each line in the file has four elements:

Module:

auth: provides the actual authentication (perhaps asking for and checking a password) and sets credentials, such as group membership or Kerberos tickets.

account: checks to make sure that access is allowed for the user (the account has not expired, the user is allowed to log in at this time of day, and so on).

password: used to set passwords.

session: used after a user has been authenticated. This module performs additional tasks which are needed to allow access (for example, mounting the user's home directory or making their mailbox available).

The order in which modules are stacked, so that multiple modules can be used, is very important.

Control Flags: tell PAM which actions to take upon failure or success. Values can be required, requisite, sufficient or optional.

Module Path: path to the pluggable module to be used, usually in /lib/security.

Arguments: information for the modules

Shadow password files are automatically detected by PAM.

More information can be found in the pam man pages or at the Linux-PAM project homepage.

10.2.9.3. LDAP

The Lightweight Directory Access Protocol is a client-server system for accessing global or local directory services over a network. On Linux, the OpenLDAP implementation is used. It includes slapd, a stand-alone server; slurpd, a stand-alone LDAP replication server; libraries implementing the LDAP protocol and a series of utilities, tools and sample clients.

The main benefit of using LDAP is the consolidation of certain types of information within your organization. For example, all of the different lists of users within your organization can be merged into one LDAP directory. This directory can be queried by any LDAP-enabled applications that need this information. It can also be accessed by users who need directory information.

Other LDAP or X.500 Lite benefits include its ease of implementation (compared to X.500) and its well-defined Application Programming Interface (API), which means that the number of LDAP-enabled applications and LDAP gateways should increase in the future.

On the negative side, if you want to use LDAP, you will need LDAP-enabled applications or the ability to use LDAP gateways. While LDAP usage should only increase, currently there are not very many LDAP-enabled applications available for Linux. Also, while LDAP does support some access control, it does not possess as many security features as X.500.

Since LDAP is an open and configurable protocol, it can be used to store almost any type of information relating to a particular organizational structure. Common examples are mail address lookups, central authentication in combination with PAM, telephone directories and machine configuration databases.

RedHat comes with a slightly improved OpenLDAP version. See the system specific information and the man pages for related commands such as ldapmodify and ldapsearch for details. More information can be found in the LDAP Linux HOWTO, which discusses installation, configuration, running and maintenance of an LDAP server on Linux. The LDAP Implementation HOWTO describes the technical aspects of storing application data in an LDAP server.